|

| Plaque commemorating H.G. Wells. (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

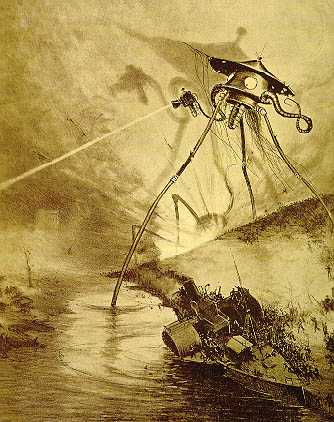

| Alien tripod illustration by Alvim Corréa, from the 1906 French edition of H.G. Wells' "War of the Worlds". (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

| H.G. Wells Book War Of The Worlds (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

| A Short History of the World (H. G. Wells) (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

| H. G. Wells in 1943. (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

I have just finished reading a biography of H.G. Wells by

the Canadian Lovat Dickson, who got to know the great writer in his later years

when he, Dickson, was working in publishing in London. It is a book I have had

for many years that has somehow survived the clearout I have made in recent

years of the thousands of books I once owned.

Of course, as I now realize, I

should have read the book years ago, for I belong to that generation for whom

H.G. Wells and Bernard Shaw were the two great sages of English-language

literature. One of my vivid teenage memories is of sitting in the library of my

high school in far off Invercargill, New Zealand, reading Wells’s last

publication, called Mind at the End of

Its Tether, a little volume written in 1945, at the end of the war which

--- although he had prophesied exactly such an explosion if the world did not

accept his prescription for a World Government, that would control all the

armed forces on earth ---- had plunged

him into despair. I cannot remember exactly what he said in that book, but

another vivid memory I have of his impact on me as a teenager is that I

remember him writing that if all the children born in England had been transferred

in infancy to Germany, and all the German children to England, each group would

have fought for the opposite side from that into which they had been born. When analysed, that convincing formulation,

for me, called into question every influence that is brought to bear on human

beings, every institution of our government, every decision one might expect

from them, and everything one might read in our newspapers, magazines, even

books. Just that one blinding statement of the obvious, which I had never

thought about before, fixed in me a scepticism about the current state of

affairs and those who were managing it, that has lasted until this day, seventy

years later. In other words I am, intellectually speaking, a child of H.G.

Wells, even though I had no idea where he came from, against what enormous odds

he struggled his way to eminence, or even the immense range of his influence,

which stretched eventually to every country on earth.

This wonderful biography by

Dickson, published in 1969, twenty-three years after the great man’s death, fills

us in on Wells’s immense output, so vast that

Dickson could not include it all in his book, but referred his readers

to the H.G. Wells Society, formed in the 1960s, which still exists, and is

planning to have a celebration in July of this year of the 150th anniversary

of Wells’s birth, and 70th of his death. I have consulted that full

bibliography, which begins in 1893, and ends 52 years later in 1945, and lists

no fewer than 156 published works. Their range is what would now be called

mind-boggling. Early in his life he had

one ambition, to be recognized as a serious novelist, and in that he succeeded

by producing some superb novels, such as the comic stories, Kipps (1905) and The History of Mr Polly (1910), two books that established him as

the poet of the working class from which he arose, but also many others which

combined his interest in science with his interest in affairs of the heart.

His mother was a lady’s maid in a

great house in Sussex, kept by a Miss Fetherstonhaugh. Mrs Wells had gathered

enough money to establish her husband, Joe, in a miserable shop in the High

street of Bromley, Kent. Dickson writes:

“All Wells’ early years up to the

age of fourteen had the background of the dusty little china shop, always on

the edge of bankruptcy, with its basement kitchen and scullery where the family

had their being all day in a sort of half-light drawn from the pavement-grating

in the front and the scullery door at the back which led on to a little paved

yard, odorous with its brick dustbin and bricked out-door privy and rainwater

tank. Mrs. Wells, who had been a lady’s maid, had the timid confused manner of

a Victorian domestic servant. Joe Wells was a jovial outdoor sort of man. He

hated the shop and kept out of it as much as possible.”

Their youngest child quickly showed signs of being a fast

learner, eager for knowledge, but his mother, trapped in the morality of a

domestic servant, was determined to get him launched into a paying career as

quickly as possible. He was not yet 14 when he was deposited at the side door

of a draper’s establishment opposite Windsor Castle, where he lived in a

bedroom over the shop with two other apprentices and an assistant, a place

where “the deadly monotony, the servility, the feeling he was imprisoned for

life in a great machine from which escape was impossible… made him seriously

contemplate the extremes of running away or suicide.” He was saved from that by the decision of his

employer that the boy was, as he wrote to Mrs Wells, “inattentive, uncivil,

dreamy, didn’t seem interested, and was singularly inept at giving the right

change,” and requested his removal.

He next spent three months in the

enchanting presence of his Uncle Williams, as he was called, an entertaining

rogue masquerading as headmaster of a small school, who treated the boy as an

equal and kept him agog with stories, before the authorities realized he did

not have the necessary qualifications as

headmaster and dismissed him, leaving Bertie once more to return to his mother.

Fr a second time he was

apprenticed, this time to a chemist, from which he absented himself when he

realized the cost of taking the necessary exams would be beyond his mother. Mrs

Wells asked the agent of the great house in which she worked to help her, and

he got the boy a place with the leading draper of Southsea, bound to a third

apprenticeship, this time of five years, after two unbearable years of which he

asked a schoolmaster he had briefly met along the way if he could possibly take

him on as an under-master. The schoolmaster remembered the boy’s thirst for

knowledge, and hired him. And all that then remained was for him to persuade

his mother that she should agree to his breaking yet another apprenticeship.

So, he got up one Sunday morning at 5 am, walked the 17 miles back to see his Mother,

spent the entire day trying to persuade her to allow him to break his

apprenticeship, and left to return to the shop, vowing that if his indentures

were not cancelled, he would commit suicide.

So began the history of the

figure we came to know as H.G. Wells, as an under-master in a village school.

His employer decided to try to make a few pounds more by having his

under-master follow a course that would train him in the new subject of science, a course from

which the headmaster could gain four pounds for a first class pass. Needless to say, Wells succeeded with a

flurry of A passes, and was offered by the Department of Education a

studentship at the Normal School of Science in South Kensington with a bursary

of a guinea a week, leading on to a possible B.Sc in science. He was eighteen,

and at the school he came under the influence of Professor Thomas Huxley, an

atheist and a friend and defender of Charles Darwin. He flourished there in the

first year, managed to get through the second, and was renewed for a third year,

but, as Dickson remarks, “literature and love and socialism had captured his

interest, and…..the bright hopes with which he had started were coming to nothing,

and he was quite conscious of it, but helpless to do anything about it… His

mind was alive and glowing, all right, but not with the facts necessary to pass

his examinations. Reading the works of the great English writers was of no use

there, and when he left the examination hall he knew that he had failed….”

He got a job as a schoolmaster in

a small country school near Wales, but he fell when refereeing a football

match, and one of the bigger boys took advantage of the opportunity and kicked

him in the back, precipitating damage to the lungs that plagued him for the

rest of his life. He spent his twenty-first birthday in bed, recovering. At the

age of 22, he embarked on his second assault on London, determined as never

before to become a writer.

Well, we know the result of that

determination. Within five years he had his first, tentative writings

published, and two years later in 1895 he produced one of his enduring

masterpieces, The Time Machine, which

even now, 120 years later, is one of his works that remains in print. The Island of Dr. Moreau followed the

next year, and after that The Invisible

Man and the next year The War of the

Worlds, and by this time, before the turn of the century, the young man was

established as a major literary force, although so far with particular skills

in scientific subjects and works of prophecy about our scientific future.

This was not enough for him. A

man of boundless energy, rather unprepossessing in appearance, a dumpy little

figure, but with an endless flow of talk, and a rapier wit that made him

excellent company, he wanted to establish himself as a master of the regular

novel. And so he used his experiences as the basis for many future works. He

was sexually voracious, and after the success of Kipps and other novels, he

embarked on a work called Ann Veronica

whose defence of the modern young woman was so frank that his regular publisher

Macmillans refused to publish it. When it was published by another firm, it was

brutally attacked in the press for the immorality of its ideas, in language

that seems hardly credible to our present ears: all he did was portray a young

woman who was as ferociously interested in sex as he was himself, who was

determined to live her life unrestricted by the mores of her particular world.

It was really nothing that wasn’t already being lived by plenty of young men

and women. But rumours began to spread about Wells’s own sexual exploits. For a

second time with a novel called The New

Machiavelli he had a manuscript refused by his regular publisher, and once

again the novel brought vicious attacks on Wells for his lifestyle as much as

for his freely expressed opinions, at the basis of which was his belief in

sexual freedom between consenting adults.

It was from the turn of the

century until the outbreak of the First World War that Wells developed, in

addition to his scientific, straight and comic novels, his interest in the

direction of society in general, the need for socialism, and the imperative need

for a change in human affairs. He joined the Fabian Society, dominated by

Beatrice and Sidney Webb and Bernard Shaw, and confronted them with a

far-reaching programme for transformation of their purpose, which was rejected

by the founders, who preferred to keep it as a debating society, rather than as

an instrument for immediate social change. So he quit the society and

thereafter followed his bliss as a prophet of future glory, if only people

would listen to him. Dickson remarks at one point that one of the

distinguishing characteristics of Wellsian thought was his contempt for

humanity, coupled with his urgent belief that mankind could have a glorious

future if only people would listen to him. The years leading up to and through

the war are peppered with works whose titles suggest the urgency of his appeal

to his fellow men: Essays in

Construction, The Labour Unrest, What are the Liberals to Do?, The World Set

Free, The Peace of the World, What is Coming?, War and the Future, one

after the other, a veritable blizzard of advice and admonition, and then in

1919, The Idea of a League of Nations. Under

his plan, every nation in the world would have been admitted to the League,

which would control all armed forces. This, of course, was more than almost

anybody else in England could even contemplate --- what, give up the Royal

Navy? --- an idea he put forward first in 1917 in a letter to wrote to The Times, who found the idea so

shocking it refused to publish the letter.

Unfortunately, once again mankind did not

follow his advice. He never believed in the national state, regarded it as an

instrument holding mankind back from its glorious potential, and more or less

washed his hands of the mess that was made, against his advice, of the peace

following the war. Throughout all these years Dickson makes it clear that Wells

was always interested in the money he could earn from his writings, of the

contracts he seems to have negotiated personally with publishers, and that he was

always seeking ways to draw attention to his latest publications. If he sold

5,000, sometimes perhaps 10,000 copies of a book, he was doing well, but then

in 1920 he took a year to produce his monumental Outline of World History, a work designed originally for schools, produced

first in 25 separate serial issues, each of which sold more than 100,000

copies. When it appeared in book form 2,000,000 copies were sold in England and

America. Subsequently it was translated into nearly every language in the

civilized world.

No one writer had ever before

attempted a work so comprehensive in its scale, and of course, it laid Wells

open to corrections and criticisms from various experts who faulted his

detailed descriptions of their specialties. Dickson quotes Lytton Strachey as

saying, “I ceased to think about Wells when he became a Thinker.” Dickson comments:

“Wells might have replied that he was writing not for Strachey but for the new

public emerging from the war who had missed some precious years of enlightenment

and had to rebuild from a shattered world a new human order.”

Though by the 1920s Wells was

probably the world’s most famous author, it is probably true to say that he had

already passed the peak of his creativity by that time. He continued to write

novels and social tracts. He produced two more astounding enclyclopedias, The Science of Life (1930) and The Work, Wealth and Happiness of Mankind

(1931). He went to Russia and America, and conducted long interviews with

Roosevelt and Stalin, contrasting their programmes and their attitudes to

modern society. The approaching war --- which he had prophesied many years

before, putting the likely date as 1955 --- filled him with despair, as can be

seen from the titles of works he produced --- The Fate of Homo Sapiens, and

The New World Order (1939), and What

are We Fighting For? (1940), leading up, almost inevitably, as his last

published work, to the aforementioned Mind

at the End of its Tether.

Dickson records that when he died

on August 13, 1946, “all the world recorded his passing.” He adds:

“For those who met at the Royal

Institution on 30 October, 1946 to honour his memory, nearly all of whom had known

him personally and had had their lives to some degree changed by him, a great

character had gone from the scene, one who had done so much to wake us up and

prepared us for the harsh rigours our century had in store for us.”

That he is not much read today --- it appears that only

three or four of his romantic novels looking into a scientific future are still

in print --- Dickson ascribes to his

being “all brains, and very little heart.” I prefer the suggestion made by

G.D.H. Cole in his eulogy at the 1946 meeting to memorialize Wells:

“…He only wanted men to behave in

their own interest with tolerable common sense…. He could not believe that men,

if they but understood, could go on behaving so foolishly; and his life as a

writer was one long effort to help them understand. If so far he seems to have

failed, that is not because he has taught us little, but because the forces he

bade us control have moved unprecedentedly fast. If, even yet, we succeed in

catching up with them no one will deserve more thanks for it than H.G.”

No comments:

Post a Comment