|

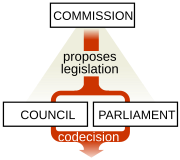

| The legislative triangle of the European Union (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

| Robert Schuman proposed the Coal and Steel Community in May 1950. (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

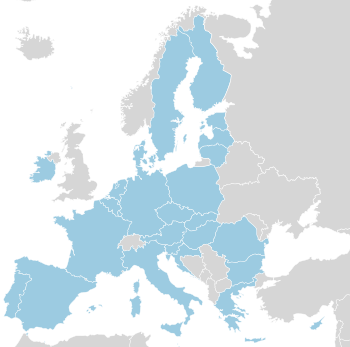

| European Union (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

It

has been obvious for many years that the European Community has been designed

to be a citadel of capitalism. Given how capitalism has developed into frank

oligarchy in so many countries in the last twenty years, this has to be accounted

the major defect of the effort to unite Europe.

Almost no sensible person could object to

the European countries getting together in an effort to overcome the repeated

wars they have fought against and between each other up to the recent past. As

we all know these wars escalated in brutality, intensity and destruction, right

up to the dreadful Second World War, with its death toll of nearly 73 million

people. The greatest wars have all broken out in Europe, more than 5,000,000 of

whose civilians died, in the last great war, to which must be added the nearly

10 million Soviet civilians killed, out of that nation’s total deaths of an

estimated 25 million. These figures are staggering, and alone provide the

impetus for the effort made since the war to establish Europe as an area

devoted to peace between neighboring states.

Europe has proceeded towards unification

in a succession of small steps, leading up to the establishment of a European

Union with an elected Parliament, voted for by the citizens of the 28 member

states, and a common currency called the Eurozone to which 19 members subscribe

(plus another six tiny entitles which are not members of the Community), and

nine do not, including the United Kingdom, Sweden and Denmark.

A feature of the way these institutions

have developed is that a great deal of European affairs are now run by bodies

appointed by these representative bodies: that is, unelected people, officials,

bureaucrats whose job is to administer the strictly capitalist rules

established to guide the development of the European economy.

A major problem has been that some

countries, notably France and Germany, are economically and politically

powerful, while many of the other 26 are small countries with less developed

economies that, thrust into this vigorous environment, are finding it difficult

to keep up or adjust. Among these are

Spain, Portugal, Italy and Greece.

Greece has been, shall we say, the

basket-case among these poorer nations, sinking into a mountain of debt which,

left-wing detractors say, was contracted not to aid the living standards of the

Greek people, but to support banks and oligarchs with loans which were simply

removed from the country into the accounts of these banks and oligarchs --- in

other words, the wealthy segment of society.

Now,

it cannot be argued that the Greeks were not, at least to a certain extent,

responsible for their own plight. Former Greek governments, including the

so-called leftist Pasok government headed by Andreas Papandreau (who spent many

years exile in /Canada during the reign of the Greek army colonels, while

talking a good case for reform while in opposition, once elected dropped the ball,

as it were, and accepted holus-bolus the dictatorship of these wealthy foreign

lenders, with the tough conditions imposed on them to ensure that all whisper

of a left-wing solution --- such ass public investment, public ownership of

resources, welfare support to the poorest, and so on, were quashed in the bud.

In the most recent example of this

draconian economic dictatorship in favour of market capitalism, the Greek

people have been reduced to penury by the austerity policies imposed by the

European institutions, headed by Germany. Headed among their punishments have

been levels of unemployment impossible for any nation that hopes to maintain

its citizenry in good health.

The left-wing political party Syriza that

has taken office since the last election a few weeks ago was formed originally

through the merger of various small Marxist groups arguing for a root-and-branch

reform that would have, at its extreme, have seen Greece renege on these massive, unpayable

debts, with the probable result that the country would be forced by the

capitalist institutions governing Europe to leave the Eurozone, with unforeseeable

consequences for the European economies.

The new government got busy as soon as it

was elected, its new finance minister, Yanis Varoufakis, who had been peacefully

teaching economics in Texas until a month or so before the election, making the

rounds of European leaders to argue their case for concessions It has to be

reported that these talks brought no sense of the entrenched powers being ready

to help the new government reform the institutions reform themselves. They were given a weekend

in which to produce a plan for reform, which if not accepted by all 26 member

states, would never be implemented.

Sure enough, they have produced a

document of some kind about which contending parties have produced very

different interpretations. The new once-fire-eating Syriza government has

suggested an extension of the present arrangements, which at least would give

them four months to work out a viable and workable programme, but in doing so

the government has undertaken “to refrain from any rollback of measures and

unilateral changes to the policies and structural reforms,” while it has been

charged with preparing “reform measures, based on the current arrangement” ---

an arrangement that Tsipras, the Greek leader, had, in his election, promised

to repudiate.

It did not take long for old-line

socialists, veterans of the decades-long struggle for economic justice in

Greece to denounce these agreements as a betrayal. Tyical was Manolis Glezos,

an old fighter for socialist justice, who said: “Some

argue that to reach an agreement, you have to retreat. First: there can be no compromise

between oppressor and oppressed. Between the slave and the occupier is the only

solution is Freedom. But even if we accept this absurdity, the

concessions already made by the previous pro-austerity governments in terms of

unemployment, austerity, poverty, suicides have gone beyond the limits.” He

added that Syriza members, friends and supporters at all levels of

organizations should decide in extraordinary meetings whether they accept this

situation.

An even more

brutal verdict was announced on the web site of

the International

Committee of the Fourth International (ICFI). They wrote:

“Even in the entire squalid history of ‘left’ petty-bourgeois

politics, it is difficult to find an example of deceit, cynicism and truly

disgusting cowardice that quite matches that of Prime Minister Tsipras.

Certainly, from the standpoint of the time that elapsed between election and

betrayal, the Syriza government has probably set a new world record. In the

hours following an agreement that is nothing less than a complete capitulation

to the European Union, Tsipras let loose another barrage of demagogic lies in a

pathetic attempt to deny the magnitude of Syriza’s prostration and to cover up

his own political bankruptcy.

“ ‘We kept Greece standing and dignified,’

declared Tsipras, in a televised statement that seemed oblivious to reality. He

claimed that the agreement with Eurogroup finance ministers ‘cancels

austerity.’ Tsipras added: ‘In a few days we have achieved a lot, but we have a

long road. We have taken a decisive step to change course within the euro

zone.’ ”

James Petras, formerly director of

the Centre for Mediterranean Studies in Athens, struck a more apocalyptic tone

in an article under the title The

Assassinaton of Greece, distributed online by the Voltaire Network:

“The Greek

government is currently locked in a life and death struggle with the elite

which dominate the banks and political decision-making centers of the European

Union. What are at stake are the livelihoods of 11 million Greek workers,

employees and small business people and the viability of the European Union. If

the ruling Syriza government capitulates to the demands of the EU bankers and

agrees to continue the austerity programs, Greece will be condemned to decades

of regression, destitution and colonial rule. If Greece decides to resist, and

is forced to exit the EU, it will need to repudiate its 270 billion Euro

foreign debts, sending the international financial markets crashing and causing

the EU to collapse.

“The leadership of the EU is

counting on Syriza leaders abandoning their commitments to the Greek

electorate, which as of early February 2015, is overwhelmingly (over 70%) in

favor of ending austerity and debt payments and moving forward toward state

investment in national economic and social development. The choices are stark;

the consequences have world-historical significance. The issues go far beyond

local or even regional, time-bound, impacts. The entire global financial system

will be affected.”

So, these are the choices as we wait to see how it all comes

out. At time of writing, the money would

seem to be on the EU bullying their way into keeping the European Union

capitalist, and no mistake.