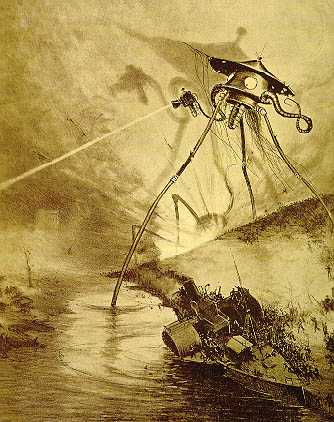

| The trunk shot is used in many Tarantino films, including Reservoir Dogs. (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

| Leonardo DiCaprio (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

| Javier Bardem and the Coen brothers (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

Before going any further I should say that since I began

to write on my own web site in 1996, I have written many more than 500

pieces. I began with what I called a

place to sound off on; I determined I wouldn’t spend any money on keeping it;

and I had been through at least three versions of the site on different

addresses, before, in 2010, hitting on the present address, on which I have

written 427 of the 500 pieces. ( Since I was more active in my earlier years, I

could probably claim to have written about 1800 pieces all told over the 20

years).

My reason for changing addresses

was that at least one of my sites was not designed for carrying this sort of web site, and was not open to

being included in the periodic sweeps made by whoever is the boss of these

things so that attention could be drawn to the site’s existence. I have stuck to my vow not to spend money on

the site, and have never made any secret of the fact that it is used just for

occasional thoughts: in other words, it is not a work of serious journalism,

which would require of me to keep more closely in touch with events. I am

retired from direct journalism, although I hope I still have the capacity to

explain what I want to say in a fashion that is clear enough to be

comprehensible to anyone.

Okay, enough of that: this piece

is about some of the recent film releases that I have managed to see, partly

because they are, unusually, now being screened in Dubrovnik, where I have been

for a few weeks. Normally in Montreal I never get to see the up-to-date releases,

because I tend to rely more on Netflix, with its offering of films I have

missed earlier, or the excellent films that are screened in the Cinema du Parc, downstairs from where I

live, which offers probably Montreal’s best selection of films of the brand

usually screened in a “film art house.”

I suppose of most interest

currently are the two contenders for this year’s Oscars, The Revenant, the remarkable film directed by Mexican director

Alejandro Inarritu, starring Leonardo DiCaprio, Tom Hardy and a cast of other

good male actors. It is about a hunting party of military men, or

quasi-military men, in 1823 in the middle of winter, that is put upon by a band

of Indians, after which, their main preoccupation is to return to their base

whole. The character played by DiCaprio is attacked by a bear when he is alone in

the bush, and almost killed. His mates fix up to carry him along with them in

their hasty retreat, but he is so severely injured and is delaying them so much,

thus opening them to even more danger of Indian attack, that they begin to

quarrel over whether they should kill him or simply abandon him to die. The latter course is chosen, and he is half

buried, and left to gasp his last, as they think.

However, he recovers sufficiently

to drag himself out of his half-grave, and thereafter shows so much initiative

in somehow managing to keep himself alive that eventually he makes it back to

camp. Probably the most remarkable thing

about this movie is that they succeeded in shooting it at all, out in the

Canadian and American winter wilderness, in terrible conditions requiring the

actors to stand in freezing water and to suffer very much what the characters

they were playing suffered. Inarritu, as

I discovered when seeing him interviewed on TV this week, looks and sounds like

the sort of man capable of inspiring his team to make extraordinary efforts,

and he appears to have done just that in

the making of this movie. I am not surprised it has been nominated for 12 Oscars,

and I expect it to be a runaway winner.

Mind you, I have little faith in the Oscars as a guide to the best movies: I felt almost personally offended in that year when Paul Thomas Anderson’s magnificent There Will Be Blood, derived from the early chapters of Upton Sinclair’s novel Oil, a movie that in my book has a claim to be considered among the best movies ever made, was beaten out by No Country for Old Men, made by the Coen Brothers, in which Javier Bardem played a homicidal maniac who went around killing people with no explanation as to why he did it, or what made him do it. It was all simply a meretricious use of insensate violence that can only be called gratuitous.

Mind you, I have little faith in the Oscars as a guide to the best movies: I felt almost personally offended in that year when Paul Thomas Anderson’s magnificent There Will Be Blood, derived from the early chapters of Upton Sinclair’s novel Oil, a movie that in my book has a claim to be considered among the best movies ever made, was beaten out by No Country for Old Men, made by the Coen Brothers, in which Javier Bardem played a homicidal maniac who went around killing people with no explanation as to why he did it, or what made him do it. It was all simply a meretricious use of insensate violence that can only be called gratuitous.

Anderson’s film by contrast,

starred Daniel Day-Lewis in surely one of the most remarkable of his many

noteworthy acting performances, as an

oil man who arrived in the American West determined to make his fortune by

persuading simple-minded farmers that he could make them rich if only they would

allow him to pump oil from their properties.

An accompanying story to that of this hard-hearted, determined bloke is

the story of a child he adopted who grew up to be unable to speak, but who,

after watching his father in action over the years, eventually decided to

strike out on his own in what he hoped might be some more morally supportable business. The denouement to this film is as

violent as anything in the aforementioned films, but the violence arose from

the main character, was bred into him, and was essential to the story; and

personally I have found that film, seen quite a few years ago, unforgettable.

One of the competing films this

year is called The Hateful Eight, another

film set in the Old West which features such an extreme level of gratuitous

violence that, as I left the cinema I remarked that “the man who made that film

is a madman.” That man is Quentin Tarantino, whose previous films have been

marked by similar levels of unnecessary and unconvincing violence. One of the

best descriptions of this director --- who for inexplicable reasons is held in

Hollywood to be some kind of boy genius --- was made by one of my sons, when he

said Tarantino’s films seem to have been made by someone who has had no

experience of life except sitting and watching TV and movies all the time.

In this film, as in the Inarritu

film, most of the action takes place in a brutal snow storm, from which the

eight central characters have sought refuge in a large country cabin. There a

diverse collection of people, one of whom is a black man played by Samuel

Jackson, quarrel, start shooting, and eventually all of them die: or maybe two

of them live, just, but seem likely to die as the movie ends. This could have been called The Hateful Film about eight hateful

people. One of the eight is a woman played by Jennifer Jason Leigh, one of

Hollywood’s most experienced actresses with a huge filmography, including many

memorable performances, but I am willing to bet she never had a roll so demeaning

as his one. She finishes the film with her face completely covered in blood sprayed

from some of the dying men, and vomit, from others, an indication of the

obscene level of violence in this terrible movie.

The third notable film I have

seen lately is The Big Short, an

effort to bring to the screen an explanation of the 2008 meltdown in the global

economy. Directed and co-written by Adam McKay, it is shot and edited in a

staccato manner that certainly suits the raid-fire production of information as

it drifts across the screen, just as it drifted across the stock markets of the

world. Personally, being myself uninstructed in the vagaries of the stock

market, I missed much of the most important information, which was rattled out

and left to die, as far as I was concerned, although no doubt younger people

with a better background in these matters must have gotten more detail out of

it than I did. I was left in do doubt,

however, that the four central figures in the film were, if not evil, certainly

extremely self-centred, criminally so, in fact, pursuing their own enrichment

and disregarding the evident disaster that would ensue for millions of people. Having learned that major banks were

gathering worthless house mortgages into bonds, they bought these bonds up, and at

the same time bet against their failure.

They couldn’t lose, except if the bonds against which they were betting

did not collapse. The central figure is a former doctor, become a fund

manager, played by Christian Bale, who eventually begins to see the error of

his ways when it is pointed out to him by a former broker who has retired in

disgust from the business, but who, when the big crash comes, stands to earn

$200 million if he sells. He considers it seriously for about five minutes, but

eventually says, “Okay, sell.” So, while portrayed as a relatively sensible centre

of this plot, he knew exactly what he was doing, realized the impact it would

have on millions of people, and yet he carried on with his schemes until the

final great payoff.

It is said in the film that six

million homeowners lost their houses, and eight million people lost their

jobs. But although it all happened

because of this monstrous fraud by the bankers and fund managers, only one

banker, an obscure functionary somewhere in Europe, went to jail. If ever the

leftist belief that capitalism is crime was confirmed, it was by by this

event. And that uncomfortable truth is not shirked in this excellent film. Some

leftist writers have objected that the film pleads for sympathy for the

evil-doers, but I didn't find that, and don’t agree with this criticism of the

film.

In addition to these films, I am

presently watching an excellent British spy-thriller called The Honourable Woman. It has eight

episodes, I am past the fifth and am gripped by every episode. It deals with an

Israeli-based company whose two young owners have invested in providing fibre

option communications to the West Bank, only to run into trouble from both

sides, plus the American and British secret security services. This has been a widely praised series, and

rightly so. But then the British are expert at this kind of drama, their

expertise reaching from the wartime drama,

Foyle’s War, a beautiful series

that is constantly being re-run, through their pitiless look at MI5, through to this new one, every bit

as expertly written, directed and acted as the previous hits.