|

| Federal CCF Caucus, in 1942 with new leader M.J. Coldwell(Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

| Clement Attlee, British Prime Minister 1945-51 (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

| Plaque recording the location of the formation of the British Labour Party in 1900. (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

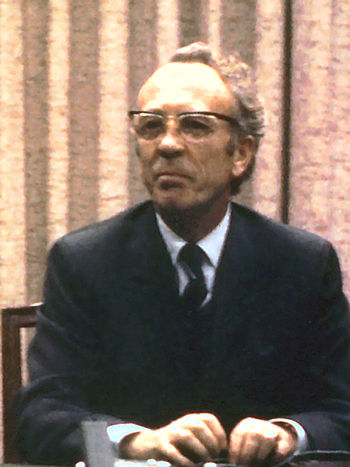

| M.J.Coldwell (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

| Thomas Mulcair, present leader of NDP(Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

| President Ronald Reagan, who began the downslide of the common man (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

| U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, who is putting the cat among the pigeons in the present US primary elections (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

| Tommy Douglas, leader of the NDP, of whom CBC viewers said he was the greatest Canadian who ever lived (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

When I arrived in Canada in 1954, having been raised under

a Labour government in social democratic New Zealand, and having, on joining

the workforce, automatically become a union member, I suppose I could have been

described as a raving socialist, and a red-hot union member.

Naturally, joining the work force

in Canada was a bit of a shock, especially since my first job was with the

notoriously anti-union Thomson Newspapers, where I first came across the

automated linotype machine to which a role of copy cold be affixed and printed

out mechanically, especially to obviate the need to hire a linotype operator

who might be unionized. In those days as a reporter, I would never have thought

of taking a picture, because that was judged, in the union contracts I had

always followed, to be the work of a photographer, and I would never have

thought of stealing his job.

Of course from the beginning I

supported politically the CCF, later the New Democratic Party, and later, when

I was working in Western Canada, I even got to interview both M.J.

Coldwell and Tommy Douglas, CCF leaders,

and my impression of both was that they would have died rather than allow the

word

“socialism” past their lips. Both, of course, were quite admirable. I was accustomed to such leaders who, while dreaming of a revolution, nevertheless trimmed what they fought for to the winds of popular acceptance. I was more or less driven out of New Zealand in 1950 by my disgust at the apostasy of Prime Minister Peter Fraser, a self-educated working class leader, who entered Parliament when in jail in the First World War for opposing conscription, and who, in 1949, returned from an Imperial Defence Conference in England where he was persuaded that New Zealand needed conscription to confront the so-called Soviet menace. Thus he split the Labour party and ensured its defeat after 14 years of good government. But not only that: he became the all-time symbol, for me, of the well-known affliction for radical leaders of the “embrace of the duchesses.” I arrived in England in 1951 just in time to join the Labour Party and lick stamps for them during the election, and then to quit in dismay after hearing my new leader Clement Attlee speak, an establishmentarian if ever I heard one.

“socialism” past their lips. Both, of course, were quite admirable. I was accustomed to such leaders who, while dreaming of a revolution, nevertheless trimmed what they fought for to the winds of popular acceptance. I was more or less driven out of New Zealand in 1950 by my disgust at the apostasy of Prime Minister Peter Fraser, a self-educated working class leader, who entered Parliament when in jail in the First World War for opposing conscription, and who, in 1949, returned from an Imperial Defence Conference in England where he was persuaded that New Zealand needed conscription to confront the so-called Soviet menace. Thus he split the Labour party and ensured its defeat after 14 years of good government. But not only that: he became the all-time symbol, for me, of the well-known affliction for radical leaders of the “embrace of the duchesses.” I arrived in England in 1951 just in time to join the Labour Party and lick stamps for them during the election, and then to quit in dismay after hearing my new leader Clement Attlee speak, an establishmentarian if ever I heard one.

So, on arrival in Canada, I never

had wild expectations of any party, but I did realize that the NDP had

performed a useful service to the country in differentiating it from the

elephant in the south, through having espoused and seen through into

legislation such measures as unemployment insurance, family allowances and

universal old age pensions. Of course, such policies were stolen by the Liberals,

which sidelined the CCF and later the NDP. The party had, to me, an unfortunate

habit of being led by Protestant ministers, but of these Tommy Douglas at least

appeared to be a man of conviction, ready to stand alone in face of reactionary

legislation as he did in opposing Trudeau’s War Measures Act imposition in

1970.

I spent the 1960s in England, but

on my return witnessed the election of a number of more or less lack-lustre NDP

leaders --- I recall my astonishment when watching the entirely admirable

labour leader Bob White dance a gig in celebration of Audrey McLaughlin’s

election as leader --- and it is no surprise that none of these leaders has

ever taken the party anywhere.

These reflections have been

stimulated by an excellent article by Michal Rozworski

and Derrick O'Keefe published in Ricochet.media,

reflecting on whether the success of Bernie Sanders in the US might presage the

end for Tom Mulcair in Canada. They contrast Sanders’s wholehearted approach to

change with the drift to the right engineered by the former Liberal Mulcair

during the recent election, and by the fact that to all intents and purposes,

Justin Trudeau’s Liberals went to the electorate with a more radical programme

than that offered by the NDP.

Nor is anything likely to change

so long as Mulcair remains the leader. He is, at heart, a Liberal, and a

wholehearted believer in the status quo, as we can see now that the mist has

cleared away from he election campaign. He has been, it is true, an effective

Parliamentary debater, and in that role played his part in exposing the former

Prime Minister Harper in such a way as to hasten his downfall. But that the

Liberals should have been willing to tax the rich, while the NDP was not,

surely tells us enough about the direction in which Mulcair is leading the

party.

That Sanders has, as the Ricochet authors write, managed to put

“socialism” back on the political agenda of the United States, where it had

been for decades almost equivalent to poison, suggests to them that Canadians

of the Left must take heed, if they are to have any chance of playing a role in

the future.

Another interesting article on Sanders

and the Left has appeared in The Guardian

by Thomas Piketty, who claims that the rise of Sanders signals the end of the

era ushered in by Ronald Reagan. Until Reagan, writes Piketty, that is to say,

in the years from the 1930s to the 1970s, “the US were at the

forefront of an ambitious set of policies aiming to reduce social

inequalities.” He recalls thatthe tax

rate for the people of highest income ($1 million or more) was for half a

century an average of 82 per cent, with peaks of 91 per cent from the 1940s to

the 1960s, and were still as high as 70 per cent when Reagan was elected. This

was accompanied by very high rates on estates, up to 80 per cent (twice as much

as in France or Germany), and these were measures which greatly reduced the

concentration of capital in the United States, and did not adversely affect its

economy.

In the context of the Canadian Left, which has been

shuffling to reduce its recognition of “socialism”, it is extremely important

to be reminded of these facts. If the United States could do it in those days,

then surely Canada could do it in these days. And by “it” I mean introduce a

coherent set of policies to reduce inequalities and redistribute money from the

wealth-owners to the people who do the actual work, the middle and working

classes, primarily through social measures such as transfers, child care, early

education, free University tuitions (which, someone has reminded us this week

would amount to no more than $10 billion a year, no more than four per cent of

the federal budget).

It is ludicrous for the right to argue that we

cannot afford measures which we could afford in 1970, even though today we have

far more wealth to distribute. This is, or should be, the essential difference

between Left and Right in politics. For the Right, with their untrammelled

market system, it is every man for himself, and the devil take the hindmost.

For the Left, all politics should be underborn by a recognition that we are

our brothers’ keepers.

Although the NDP has a good record of having

stimulated progressive measures implemented by other parties, they are showing

no evidence at the moment that they are thinking about what is going to be

needed in our new age of technology and accumulation of wealth, if life is to

remain liveable for every one of us.

No comments:

Post a Comment