|

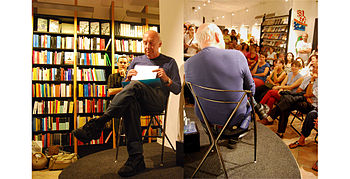

| Writer Eduardo Galeano during a conference at the Librarsi bookshop in Vicenza, Italy. (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

| Open Veins of Latin America (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

| EDUARDO GALEANO (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

I count myself extremely lucky to

have heard Galeano speak in person, during one of his visits to Ottawa a few

years ago. He was an amused and amusing man, it seems, good humoured,

insightful, and still, although getting on in years, full of fire. The book of

his that is most spoken and written about is called Open Veins of Latin America which reached its greatest notoriety when Hugo

Chavez formally presented a copy of it to Barack Obama at an international

conference. Sales of the book soared overnight,

and it is still recognized as one of the most influential books ever written on

the politics of Latin America, although Galeano, who apparently wrote it at

white heat, later said he found it rather stodgy, looking back at it. I have not read that book, but I believe his

trilogy is the greatest book I have ever read. It deals with the history of Latin America

(although it dips, from time to time, into North America as well). The form of the book is unusual, to say the

least. It is comprised of short, 500-word pieces, each of them inspired by some

passage he has read in someone else’s work, identified by a number at the end

of the piece that can be checked against the inspirational source at the back

of the book.

These pieces are certainly not taken

from these cited works: they are wonderful little essays by Galeano about some

incident or person, some triumph or tragedy, some heroism or villainy, drawn from history. The form is wonderfully suited to someone

with his prodigious memory and knowledge, which enables his history book to be both

searingly intense and intensely amusing. All sorts of characters, most of whom

his readers have never heard of, wander in and out of his pages, either inspiring or horrifying his readers,

depending on what we bring to them. History books were never like this.

The first volume begins in

pre-history, deals with pre-Columbian years, and takes us up to 1700 or so. By

the end of the first chapter one is not only dazzled, but infuriated by such

inhumanity to man (and nature). The second volume takes the story through the

nineteenth century, and leaves the reader limp with anger, and by the end of

the third volume, which covers the

twentieth century, one is awakened to

the fact that these terrible things that have been visited on Latin America

through history, mostly by American and European capital, but also by their

local compradors, are still going on as we sit reading about them.

It was these compradors who ensured

that even the winning of freedom by Latin American countries from the yoke of

Spanish and Portuguese domination hardly improved matters: American and European,

mostly British, capital was waiting in the wings, ready to swoop on these

newly-liberated nations, and they did swoop so successfully, using their local

satraps, as to make the change in ultimate control more or less meaningless:

the massive rape of the continent went on, uninterrupted.

Galeano was born in 1940, had to leave high school after two

years, became a journalist, and thus was self-educated, his education including

about 12 years in exile from military dictators who wanted to kill him. When he

returned to his home country of Uruguay and plunged into writing a form of

writing that was more demanding than the journalism in which he learned his

trade, his work mellowed, became gentler, less angry, but no less relevant to

his continent and its woes. He always had a great interest in people who never

made it into the history books, people, as he once described them with that

touch of irony that was typical of him, “who don’t speak

languages, but dialects. Who don’t have religions, but superstitions. Who don’t

create art, but handicrafts. Who don’t have culture, but folklore. Who are not

human beings, but human resources. Who do not have faces, but arms. Who do not

have names, but numbers. Who do not appear in the history of the world, but in

the crime reports of the local paper. The nobodies, who are not worth the

bullet that kills them."

A few years ago

he wrote a book called Mirrors, celebrating

people who had been forgotten by history, but should not have been. I remember

particularly his tale of a man who, when involved in negotiating the U.S.

Declaration of Independence, tried mightily to have included in it a

declaration forbidding slavery. He failed, of course, and thereafter his name

was written out of all history of the period.

For some time now

my current partner in life has enlivened each day by sending to my computer a

little item from Galeano’s throw-away book Children

of the Days in which he records some piquant item from historical or

contemporary life for each day of the year. As a book it reads rather as if

composed of items he didn’t have room to include in Memory of Fire but that he

didn’t want to lose entirely. Here is a typical one, under the heading, The Discovery:

In 1492 the natives discovered they were Indians,

they discovered they lived in America,

they discovered they were naked,

they discovered there was sin,

they discovered they owed obedience to a king and a queen from

another world and a god from some other heaven,

and this god had invented guilt and clothing,

and had ordered burned alive all who worshipped the sun and the

moon and the earth and the rain that moistens it.

That’s Eduardo

Galeano, encapsulating in a few words a great message we all should learn.

No comments:

Post a Comment