| The government building in the centre of Sarajevo burns after being hit by tank fire during the siege in 1992 (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

| Slobodan Milošević, Alija Izetbegović and Franjo Tuđman signing the Dayton Agreement in Paris on December 14, 1995. (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

| Animated map of the Yugoslav Wars. (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

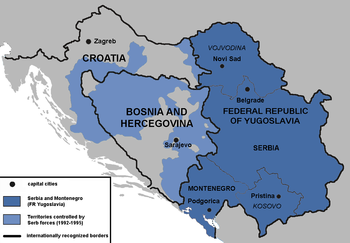

| Territories of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Republic of Croatia controlled by Serb forces 1992-1995. (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

I was a little hesitant about writing

such a piece because the trigger for it was the appallingly bad behaviour of

the Aussie cricket team after defeating New Zealand in the final of the Cricket

World Cup. This was a victory that I had taken to be inevitable and it occurred

because of the superior skills of the Australians. But still, beginning on such

a basis, a piece along those lines could hardly help but degenerate into

arguments that, frankly, must be nationalistic. While I was still mulling over

this idea I picked up a book that was lying around in the Croatian household in

which I am currently staying, called Seasons

in Hell: Understanding Bosnia’s War. Published

in 1994, the book was written by

Ed Vulliamy, a Guardian reporter who covered what is known to the outside world as

the Yugoslav war, that raged through most of the 1990s, and was brought to an

end in 1995 with the Dayton Agreement, cobbled together by the international

community that can now be said to have signally failed to rise to the grave

circumstances with which the war confronted them.

This was a war in which nationalisms

raged even among people who had lived peaceably side by side for decades, even

for hundreds of years, but who began, under the influence of these

nationalisms, to perpetrate almost indescribable barbarities on each other. I

had only to read Vulliamy’s first chapter, entitled War of Maps, to abandon any idea of writing anything that might

carry even a whiff of nationalism, which

has never before --- at least not in modern times --- demonstrated so

clearly its poisonous qualities.

Vulliamy writes that the

commonly-held idea that the war was too complicated to understand was a

complete fallacy. “Bosnia’s war is cruelly simple,” he writes. “It is the

result of the resurrection in our time of the dreams and aggrieved historical

quests of two great Balkan powers of medieval origin, Serbia and Croatia, and

the attempt to re-establish their ancient frontiers with modern weaponry in the

chaos of post-communist eastern Europe.”

Caught between them was a third

people, who historically speaking did not belong anywhere, and these were the

Slavic Muslims, converted during the longish Ottoman occupation of the area,

and mostly resident in the third entity, Bosnia, which was about equally shared

between Serbs, Croats and Muslims.

The war was between what he called

two narods that being a Slavonic word

that means “a people” and “a nation” at

the same time. Once the demons of these nationalisms were released --- the main

agitator being Slobodan Milosovic, a

rising Serbian politician who rode his horse right into the presidency of what

was still called Yugoslavia --- civilization as we think of it virtually

collapsed. “You hear it everywhere in Yugoslavia nowadays,” Vulliamy writes,

“the Hrvatski narod, the Croatian

people; the Serpski narod, the

Serbian people; and also the Bosanski

narod, the Bosnian people,….and, of late, the Mussulmanski narod, the Muslim people, too.”

At an early stage of his coverage of

the war, Vulliamy found that if he asked a question about yesterday’s artillery

attack, the answer was quite likely to begin in the year 925, “invariably

illustrated with maps.” That is why he

called it “the War of Maps.” Historically, wave after wave of outside

conquerers had swept through the entire territory, Christians of Charlemagne’s

Roman Catholic empire coming from the west, eastwards, and the Orthodox

Byzantine emperors coming from the east, sweeping westwards. The principality

of Serbia “emerged under the tutelage of Byzantium”, and evolved into a

powerful independent kingdom under its own Emperor up to 1346, but in the

following century was “buried under the Turkish advance,” leaving behind in

Serbia’s former empire “a vigorous cultural nationalism which has since refused

to die.”

For their part, the Croatians had

first accepted the suzerainity of the Christian Charlemagne, but were later

overcome by the advancing forces of Byzantium. In 924, however, a Croatian

king, Tomislav, freed himself from the two dominating influences and

established himself over a vast area reaching as far north as the Hungarian

border, and east towards what has become Serbia. Some of the maps that were

revived on both sides when the modern war was breaking out, show his borders reaching

even further. But his empire lasted only three years and was quickly absorbed

into the Hungarian rule.

The result of this plethora of maps

is that Serbia and Croatia, both obsessed with their past, both of them stewing

over indignities visited on them in history, each claimed borders that

overflowed their neighbours’ claims.

The context of the war, he writes,

was the surge of popular revolutions against communist tyranny that followed

the falling of the Berlin wall in 1989, the Yugoslav narod being only two or three of about a dozen from Russia,

Slovakia, and other modern nations (Ukrainians, Georgians, Armenians, all of

which have rebelled from overlord rule,

being among them.)

The rest of Vulliamy’s book describes

his horrendous experiences as he covered the war for more than two years. He

did not follow the old rule that no story is worth dying for. Appalled by the

brutality with which the Serbs carried out the “ethnic cleansing” of

territories in which they were the majority population in Bosnia, this reporter

attached himself to convoys of people who had been subjected to the ultimate

indignity, not for anything they had done but just because they actually

existed. He describes the methods used

by the bully boy army of Serbian-Bosnians led by the psychiatrist Milovan Karadzic, and his leading general Ratko

Mladic, neither of whom can be described as fully sane. These methods went

something like this: a unit would lob a grenade into a house in which people

were probably living an ordinary life, then they would enter the house, begin

beating the inhabitants mercilessly, probably killing most of the able-bodied

men, then they would turn those who were left --- usually women, children and the

aged --- into the streets, tell them to head in a certain direction and never

to turn back. Along the way, sometimes travelling in their own cars, sometimes

in buses and trucks, often walking, they would be fired upon, spat on, beaten,

and finally robbed, so that they became a walking mass, heading into the

forests in an almost vain hope that they were heading towards people who might

welcome and save them. Behind them the attackers would have driven trucks to

the houses to strip them of their contents before setting fire to them, or

blowing them up. Or, in certain houses too good to blow up, to move into them.

Needless to say, in this disgraceful

human landscape, Vulliamy encountered some people who showed heroism in face of

these brutalities, some younger people who exhibited undoubted qualities of

leadership which emerged simply under the pressure of events, and he does full

credit to them. He also mentions that of

150,000 Serbs who were living in Sarajevo before the Serbs put that city under

a four-year siege, some 90,000 never left, but stayed to defy the best efforts

to displace or murder them, by their fellow-Serbs.

I had not realized before that there

were actually two wars fought over Bosnia. The first by the Bosnian-Serbs

(reinforced by the Yugoslav army, the fourth most powerful in Europe, which

became a weapon in the Serbian armoury), a war fought as they battled to expel all Croats and

Muslims from the territories that they fully expected to absorb into a Greater

Serbia (they actually formed a Serbian Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina, which,

in the eventual settlement, was recognized by the international community as

the Serpska Republic, a semi-autonomous area within the republic of

Bosnia-Herzegovina.) The second war was

fought by a Fascistic army of Bosnian-Croats, most of them emanating from

Montenegro in the south, who changed their minds in mid-battle and joined the

Serbs in ethnically cleansing the Muslims from the territories that they, the

Croats, fully expected to absorb into the state of Croatia. (In fact, these Croats,

like the Bosnian Serbs, formed their own, never recognized republic which they

called the Croatian Union of Herzeg-Bosna).

Each of these entities formed their own army, and the state of

Bosnia-Herzegovina also managed to cobble together an army to try to defend

their abandoned citizens. He records that each of these sides at various times

committed unpardonable atrocities, but that most of these were committed by the

Serbian and Croation ethnic cleansers.

If readers have formed the opinion

that this was a dog’s breakfast, they may be pardoned for doing so. But Vulliamy

shows that such emphasis on the past, on the blood of the narod, such concentration on the injustices worked years and even

centuries before on your group, had their impact in the present day on the poor

people who were rooted out of homes that were destroyed as soon as they left

them, and who were left to wander aimlessly, until most of them wound up in

existing cities, or in expanded villages, where (as in the infamous case of the village of Srebrenica, which must

have happened after Vulliamy ceased to be an active correspondent there,

because he doesn’t mention it in the book, Muslims were promised shelter by the

UN, whose soldiers then stood aside and watched as Mladic’s army massacred an

alleged 8000 men).

I have visited Sarajevo, once a

proudly racially-mixed city, now one that is racially-divided, as everywhere

else in the former Yugoslavia is; I passed through Mostar, whose ancient and

much-prized historical bridge over the river was wantonly destroyed by Croatian

guns in their quest for a racially-cleansed city (which, needless to say, they

have succeeded in creating, the Muslims now being confined to “across the

river”, while the Catholic Croats occupy the rest of the former town).

The lessons of these wars, and of

this book, is that nationalism is poison as a guide to action. And it is deeply

ironical that in this age in which we know more about everything than human

kind has ever known before, our populations everywhere seem to be breaking into

smaller and smaller groups, each of them occupied by a narod of some kind, determined to defend its space against

surrounding possible-enemies. I can count at least half a dozen units that have

been established from breakaways in Europe, as many in the former Soviet Union,

and as many again in Africa and the Middle East. (In this latter region, there

seems to be some sense in the upheavals, because their borders were dictated by

the colonial powers, and took no notice of ethnicities, cutting them in some

cases --- the Kurds are an excellent example --- between three, four and even

more states.

An example closer to our own backyard

is the failure of the Federation of the West Indies, since broken into a

plethora of tiny states that have proven vulnerable to drug-trading criminals

and the like, and many of which cannot summon the strength even to defend their

own indigenous cultures.

These nationalisms are a curse, and

nowhere is that clearer than in the former Yugoslavia, whose people turned on

each other ferociously, and for all their killings and betrayals appear to have

received no benefits except national passports and borders, erected at the very

moment that in the rest of Europe such impediments to free movement have come

down.

No comments:

Post a Comment