|

| Land-use planning in action (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

| Canary wharf tube station 2003 (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

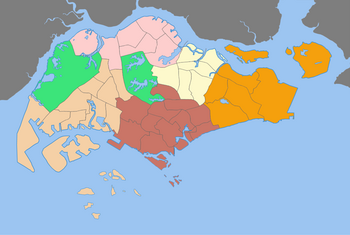

| Singapore. Planning regions. (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

| Suburban development in Colorado Springs, Colorado (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

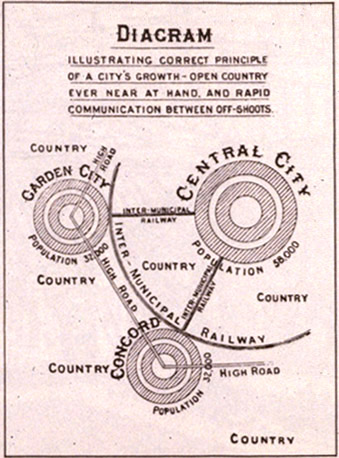

| A 1902 example of city planing (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

| An urban landscape: Hong Kong overlooking Kowloon (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

Within a few years I had realized there were other things

in life, and as my so-called career (that is another story) developed, I became

a sort of half-assed expert on urban and social problems, writing a lot about

how cities were built and controlled under various social systems, and always

keeping in the back of my mind my preference for some form of socialism as the

only possible method by which the opportunities for most people in life could

be equalized.

My so-called expertise advanced at one point to the level

at which I was asked to speak at various conferences dealing with urban

planning, city development and so on. I was cruelly aware of my inadequacy when

speaking to a roomful of experts but I tried my best, and tried to make as many

jokes as I could --- usually rather

painfully obscure jokes --- to keep things lively.

Having written a newspaper series on the development of

Montreal’s suburbia in the late 1950s, and having examined things in

Scandinavia (whose use of public ownership of urban land particularly impressed

me), Holland (whose every inch of land seems to have been carefully planned) and

Britain (where in the 1960s I covered, and was hugely influenced by, a huge

World Congress of Architects, with representatives from 124 countries), my

inclinations led me when I returned to Canada in 1968 after eight years as a

correspondent in London, to write about Canadian cities in the late 1960s and

early 1970s, at which time I found to my surprise that most Canadian cities had

no idea what was happening in other parts of the country. So my first published

book was a sort of expanded version of those articles under the somewhat

pretentious title of The Future of

Canadian Cities, a title provided by my publisher, New Press, whose co-owner

Roy MacSkimming, showed such enthusiastic support for my work that he launched

me into book-writing, that has eventually led to some seven titles on various subjects.

Once again I was cautiously aware of my

inadequacies on the subject, and I remember the scorn with which the book was

reviewed by at least one of the panjandrums of Canadian planning. My only

defence could be that it wasn't intended for the experts in the subject, but

for the ordinary guy in the street who might be interested in what was being

built around him.

Eventually, when I had embarked by accident on a career in

documentary films, I was entrusted with the direction of a film intended to be

screened at the opening of the UN Habitat conference in Vancouver in 1976. In 1975 my wife and I decided to retire to

New Zealand, and I remember that part of the decision came from my feeling of

inadequacy before the task of making that film. I returned from New Zealand twice

in the following 12 months, and on one of those visits conducted interviews for the NFB with leading

world authorities attending the Vancouver conference. (My main memory from

these interviews is that in one of them, the fellow I was interviewing, acknowledged

to be the world’s leading expert in housing for the poor in Latin America, was

so dull that I actually fell asleep for a few seconds, during the interview.)

The subject I had chosen for the film that I ran out on was the huge migration

under way everywhere to urban areas. It was so relevant that people are

continuing to write books about it almost 40 years later, because alone, this

one global event, the migration to the cities, has overwhelmed almost every

heavily-populated nation.

When today Beijing is being planned as the centre of a

single metropolis that will contain 135 million people, it can easily be

understood how the scale of this

unimaginable migration has changed everything to such an extent that all my

previously hard-won knowledge seems now to be more or less useless.

In recent months The Guardian newspaper in London has been publishing

a remarkable series of articles on these new cities under such titles as Which

is the world’s most vulnerable city? Which

is the hottest city? Which is the most expensive city? And so on. Needless to

say the series has taken full account of the changes under way already as a

result of global warming, with its resultant increase in the level of the

oceans. For example, apparently St Mark’s Square in Venice, one of the world’s

architectural urban wonders, now is flooded 100 times in every year. (My main

memory of St. Mark’s is that while we were sitting there, a distressed young

mother who had lost her child came rushing by shouting, “Francois, Francois,

Francois!”).

What I learned from that international Congress of Architects

that I mentioned above was how the

social atmosphere in a country influences the style of architecture practised

therein. The Chinese and Russians, both preoccupied in 1960 with building

massively to house their millions of people, still recovering from the

devastation of war, were unashamedly building rather ugly residential blocks

full of tiny apartments in which families were grossly overcrowded. But at least

they had somewhere to live. But these were built in response to the need to

give homes to millions of people.

The Cubans, having not long before adopted a Communist

form of government, turned up with plans for and photographs of neat,

attractive, bungalows built by their government, houses that were made to look

attractive by being painted in a variety of pastel colours. Britain, which

after the war was also confronted with replacing destroyed neighbourhoods, had

built tower blocks that they regarded as the latest thing in sophisticated urban

planning, blocks surrounded by green spaces in which children could play safely

--- a form of housing that, with use, began to show deficiencies that have made

them almost a by-word in mistaken urban development. But it was no accident

that this form of development should have been practised by the British, who,

with their strongly Labour city councils following on the six years of Labour party government that ended

in 1951, rather stood somewhere between the left-wing and the right-wing

governments. The architects in the more conservative countries, on the whole appeared to be notable more for

their monumental architecture --- theatres, museums, universities and the like

--- than for that profession having been placed at the service of utility. The British, expanding their education system

on a democratic basis, had developed a form of school building known as CLASP,

which comprised prefabricated units that were easily fitted together in various

shapes, sizes and colours to lend an air

of quality to even schools that were

hurried into place in this way --- once again, the architectural styles being at

the service of the social system.

One of the central themes of the Congress was the exciting

and revolutionary new uses to which reinforced concrete was being put in Italy

and South America whose architects had

invented totally unprecedented spans of concrete roofing made up of thin layers

of concrete reinforced by networks of steel supports.

Many years later I had the opportunity to observe from

close up some of the planning principles observed as the Chinese Communist

regime rebuilt their cities so as to accommodate industries and the workers who

kept their factories humming over. Although,

as before, the actual apartment buildings were quite ugly, they were needed in

such vast numbers that their utilitarian air was hardly to be wondered at. And

in many ways the way of life imposed by the Communist regime on their city workers

seemed almost ideally suited to their

needs. Unlike in Canada or any

other western country, they did not go in for industrial parks on the edges of

cities, divorced from the living places

of the workers who need cars to get to work along highways the building of

which constitute one of the main costs of government. Nothing like that in the

Chinese cities I saw during a film-making visit in 1978. The factories were

built in the middle of the cities, as were the houses. Side by side. Hardly any workers lived more

than a half-hours’ bicycle ride from their place of work, and this use of the

bicycle as the primary means of mobility

appeared to be one of the things

that kept he population so fit. I

don’t think I saw a fat person during my three-month stay there. Every shift

change, morning and afternoon, the broad city streets were thronged with

thousands of people making their way to or from work. ……each factory had a

bicycle park capable of handling up to 4,000 bicycles --- an amazing system to

our western eyes, yet one that seemed to be run with remarkable efficiency.

I did think, at the time, watching how well the various

elements of this system jelled together, that if ever they discovered the automobile,

they would be in deep trouble. It never occurred to me that within twenty years

their cities would have been so completely transformed into glittering,

western-style conglomerations full of towering skyscrapers, the streets

surrounding them clogged with the inevitable traffic jams.

When I first began to interest myself in urban places, my orientation

came from the sort of knee-jerk leftist

thinking that included such ideas as urban renewal, by which was meant the

clearing away of slum areas and their replacement with modern apartments. The

inevitable accompaniment of such thinking was a sort of linear planning that

arose more or less naturally out of the destruction created by war. For example,

the city of Coventry in England, where I worked for a year, was badly damaged in the war, and their

leftist city council set out immediately the war was ended with a full-scale

reconstruction plan that they insisted on fulfilling year by laborious year. (I

should perhaps have mentioned that as a child I grew up in a country in which a Labour government

undertook a huge State housing scheme which provided for building cottages in

featureless streets and rows, many hundreds of which my building contractor

father obtained the contract to build in my home town. It never occurred to me

that these were anything but a good thing, designed to uplift the quality of

our common lives, and we were quite shocked when the renowned Welsh architect

Clough Williams-Ellis, who had constructed a fairy-tale village on the Welsh

coast, came to New Zealand and delivered a trenchant criticism of our beloved

State housing scheme. I remember that

our minister of housing, a working-class

man with limited education but a colourful vocabulary, responded, “We don’t

need to take lessons from any snuffling snufflebusters from the old country to tell us how to build

houses.”)

Just what has happened to these simplistic verities I

absorbed in my youth I have no idea. I

do know that in every country in which I have studied the matter, homes cannot

be built for the poorest people who need homes the most, without some form of

government subsidy. Some brave efforts have been made in Canada, some of them

right here in Montreal, in the 1960s and

1970s to prove that that was not so, but none of them really succeeded. Similarly,

many people with a social conscience who have found themselves owners of, for

example, hotels occupied by poor tenants, have vowed to improve the conditions

of life in the hotel, without forcing the tenants out. But to be best of my

knowledge, none of these schemes has ever succeeded: the inevitable consequence

of upgrading accommodations is that the people living at lower rents in the old

standards have not been

able to afford the higher rents for the upgraded places,

and have had to move elsewhere.

That may not be just, but who said life was just?

Don’t tell me I am reduced to such cynicism by my

experience of urban life. It’s probably just that, even in such small efforts as

these, the basic conditions of life assert themselves, those conditions that

have always bedevilled the quest for workable socialist solutions. If most of

the money is in the hands of the wealthy class, they are certainly not going to

volunteer to give it up so that poor people might be rescued from their misery. So how do we get our hands on some of their

wealth and put it to a more socially useful purpose? The only countries where I have seen that

coming even close to working is in the socially-conscious nations of Scandinavia,

whose extremely heterogeneous populations have been ready to pay half of their

incomes in tax, knowing that they can expect a better standard and quality of

life.

I’m afraid consideration of these knotty questions will

have to await another day.

No comments:

Post a Comment