|

| P. G. Wodehouse, at 23 (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

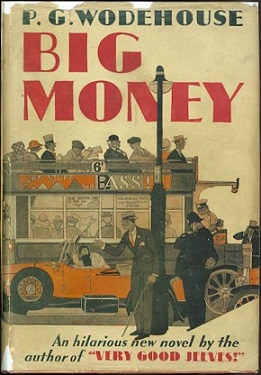

| 1st US edition (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

For many years I have believed that the following

paragraph is probably the greatest

opening paragraph ever to grace an English-language novel:

“While I would not go so far,

perhaps, as to describe the heart as actually leaden, I must confess that on

the eve of starting to do my bit of time at Deverill Hall, I was definitely

short on chirpiness. I shrank from the prospect of being decanted into a

household on chummy terms with a thug like my Aunt Agatha, weakened as I

already was by having had her son Thomas, one of our most prominent fiends in

human shape, on my hands for three days.

“I mentioned

this to Jeeves, and he agreed that the set-up could have been juicier….”

I am brought back to this favourite topic of mine, the

Jeeves and Wooster novels of P.G. Wodehouse, by the absolutely superb biography

of the master written by Robert McCrum under the title A Life of P.G. Wodehouse, published to wide acclaim in 2004, and

picked up by me in excellent condition for a minuscule $10 from The Word bookshop, of whose proprietor Adrian

King-Edwards, someone remarked this week that he is more like the curator of a collection

than a bookseller.

I am sometimes accused of having

gone overboard in my enthusiasm for the Wodehouse prose style. But look at that

first paragraph quoted above: it is amazing. Within the six or seven orthodox

lines of a perfectly straightforward English prose construction lie at least

half a dozen almost unimaginable

syntactical bombs: first, “starting to do my bit of time at….”, an

expression normally reserved for imprisonment; second, “I was definitely short

on chirpiness…” a throw-away semi-slang expression at odds with the formal

setting in which it is found….; third, “being decanted into a household…” an

expression usually used for pouring wine into a carafe; fourth, “ with a thug

like my aunt Agatha…”, an expression almost unimaginable as a description of an

Aunt; fifth, “one of our most prominent fiends in human shape…”, an unheard of

description of a small boy; and sixth, at the beginning of the next para, “the

setup could have been juicier…”, on a surface an expression so ludicrously

inappropriate to the use to which it has been put as to be so funny as to make

one laugh out loud.

This is a perfect example of what

Mr. McCrum on page 253 calls “Wodehouse’s marriage of high farce with the

inverted poetry of his mature comic

style.” Seven pages later McCrum

describes Wodehouse’s reaction to being told that on June 21, 1939, he was to be awarded an

honorary doctorate of literature by Oxford University, an honour that, wrote The Times editorially, weighing into the

considerable debate that had followed the announcement, was unquestionably

deserved, because “everyone knows at least some of his many works and has felt

all the better for the gaiety of his wit and the freshness of his style.” Wodehouse

himself said, “I had no notion that my knockabout comedy entitled me to rank

with the nibs.”

But a page later Mr. McCrum has

discovered among Wodehouse’s vast writings an amusing description of a walk taken by him the day before that

momentous occasion with the famous literary man, Hugh Walpole, who, as they

walked, alluded to Hilaire Belloc’s

recent judgment that Wodehouse was “the best writer of English now alive.”

“He

said to me,” wrote Wodehouse in his memoir Performing

Flea, ‘Did you see what Belloc said about you?’ I said I had. ‘I wonder why he said

that.’ ‘I wonder,’ I said. Long silence.

‘I can’t imagine why he said that,’ said Hugh. I said I couldn’t, either.

Another long silence. ‘It seems such an extraordinary thing to say!’ ‘Most

extraordinary.’ Long silence again. ‘Ah, well,’ said Hugh having apparently

found the solution. ‘the old man’s getting very old.’ ”

This is a perfect example of

how Wodehouse would make everything that he was describing seem like a

comedy. In fact, the description of the ceremony at

which Wodehouse was honoured does sound highly comic, with the university’s

Public Orator presenting Wodehouse to the Vice-Chancellor with “a brilliant and

witty celebration of Wodehouse’s gifts composed in faultless Latin hexameters,”

in which he made ingenious references to Bertie Wooster, Jeeves, Mr Mulliner,

Lord Emsworth, the Empress of Blandings, Psmith, and Gussie Fink-Nottle. He

then described Wodehouse in Latin, as

“wittiest of men, most humorous, most charming, most amusing, full of

laughter.” Later, at the culminating dinner of 400 guests, all impeccably

dressed in white ties and waistcoats (except Wodehouse, who wore a dinner

jacket), the undergraduates banged the tables and demanded a speech from

Wodehouse. “The new Oxford man,” records McCrum, “author of some of the funniest

books in memory, rose awkwardly to his feet. If the guests were hoping for a

comic tour de force, they were to be disappointed. Wodehouse simply mumbled,

‘thank you,’ and sat down in confusion.”

A recurring

theme in McCrum’s book is how unmemorable Wodehouse was in person, one person

after another being quoted who found him, frankly, dull. Alec Waugh, for

example, brother of Evelyn, and himself a popular novelist, wrote of meeting

Wodehouse: “He had no peculiarities or manner of expression. He was not funny.

He never repeated jokes. There was no sparkle in his conversation. He did not

indulge in reminiscences. There was a straightforward exchange of talk… ‘It is

an extraordinary thing,’ he would say, ‘Marlborough beat Tonbridge and Tonbridge

beat Uppingham, but Uppingham beat Marlborough. What do you make of that?’ ”

Yet Waugh remarked on how easy he felt in Wodehouse’s company, and how he could

recall “only the pleasure of his company.”

Wodehouse

was one of four sons of one of those incredible British families, raised in the

so-called public (that is, private) schools, especially to administer the

British Empire, who simply drifted off around the world, leaving their children

behind to be looked after by someone else. He records that first the new baby (somewhat

eccentrically named Pelham, like his brothers Armine and Peverill), born in

1881, was looked after in Hong Kong, where is father was a magistrate, by a Chinese

nursemaid, but before he was three he had been brought back to Britain and

deposited with a Miss Roper. He did not see his mother again for three years,

and Mr. McCrum records that between the ages of three and fifteen, the child

spent barely six months in the presence of his parents. “The psychological

impact of this separation on the future writer lies at the heart of his adult

personality,” McCrum writes. Somehow or other the boy survived: “the damage

inflicted on him in childhood was counterbalanced by his exceptional good

nature, and the light, personal sweetness that all those who knew him comment

on.”

The writer

says of his subject: “his childhood made him solitary, but his genius --- the

word is not too strong --- made the solitude bearable and transformed its

fantasies into high comedy.” He also adopted defensive strategies of evasion,

one of them being constant travel. He could seldom settle anywhere, was always

changing houses, made countless trips across the Atlantic (the fare was a mere

ten pounds in those days), where he found editors willing to pay him more than

in England, and got into writing for the stage. Before he finished, he was said

to have contributed to more than 50 musical comedies, usually as a lyric

writer, but also quite often as author of the book. He recorded in his memoirs:

“My father was as normal as rice pudding. My childhood went like a breeze from

start to finish, with everybody I met understanding me perfectly while as for

my schooldays at Dulwich they were just six years of unbroken bliss.” What a

lie!

He became

what is called today a workaholic, always writing, day and night, month after

month, no sooner one work finished than he was busy on another, so that by the

time of his death he had published almost 100 books, in addition to his

extensive work in the theatre. But the nature of those books is what counts. They

described a world that really never existed in actual fact, but that became so

familiar to his readers that they could never get enough of them. Although he

was enough of this world to manage a busy, successful career for more than

seventy years, there was also about him some sort of disconnection with what

most people would call reality. Not long before the Second World War he wrote

that “all this alliance-forming” reminded him of form matches at school. “I can’t

realize this is affecting millions of men. I think of Hitler and Mussolini as

two halves, and Stalin as a useful wing forward….anyway, no war in my lifetime

is my feeling.”

Famous last

words! Wodehouse owned a house in Le

Touquet, just south of Boulogne on the Channel coast of France, close enough to

London that he could indulge his restless nature by moving back and forth

easily. He was staying there as the German armies began their assault on France.

Like most other people he believed he was safe behind the Maginot line, but

eventually he had to face up to the fact the Germans were on their way. Twice

he tried to move, but both times he was stymied by mechanical breakdowns, and

in the event he was captured by the Germans ---

typically, he makes a comic scene of it in his description, quoted in

this book --- but when they placed him in an internment camp, the laughter

stopped. He was moved a couple of times, but when the Germans realized they had

in their captivity a famous British author, they released him from such direct

internment, and moved him to Berlin, where after a slight delay, they asked if

he might be interested in recording some talks for them to broadcast on the

radio. They whistled up two Germans whom Wodehouse had known in Hollywood, to

help make him feel at home, and these men helped inveigle him into doing the

talks. He himself thought he would take the opportunity to pay tribute to the

stiff-upper-lip manner in which British detainees behaved. He had no idea that

just by appearing on the Nazi radio, he was labelling himself a traitor in

English eyes, and almost before his talks --- which were intended originally

for the United States --- had been broadcast, a media onslaught against him had

begun in London.

Foremost

among these was William Connor, the acid columnist Cassandra of The Daily Mirror, whose bitter diatribe on

the BBC against Wodehouse attracted more unfavorable comment than favourable

from listeners. An early defender was George Orwell, whose childhood had been

not dissimilar from Wodehouse’s, but the broadcasts, however innocuous their

subject might have been, were a fatal error of judgment, and their fallout were a blight that hung over

Wodehouse for the rest of his life. For some time he was accommodated by an

anglophile German woman, Baroness Anga von Bodenhausen at her country estate,

where he, typically again, soon became Oncle Plummie to the children, and a

family favourite (although his wife Ethel, a more aggressive, bustling,

self-interested person, one of whose functions in life had been to spend much of

Wodehouse’s hard-earned money, was not a favorite). A revealing anecdote

illustrating his air of being out of

touch with reality is that of a young German journalist who was asked to talk

to Wodehouse. He found the writer wanted to sue some of the perpetrators of the

slanders emitted in England. “I need a lawyer I can talk to here who could then

plead for me in England. Would you know any?” he asked Michael Vermehren. “Mr.

Wodehouse,” said Vermehren. “I do know such lawyers, but do you think it is

likely that they would get a special permit to cross the war zone and the

frontiers and go to England and plead your case?” Wodehouse replied, “Do you

think it would be difficult?” “I said, ‘Actually I think it would be completely

impossible.’”

This man

later became a close friend of the writer, as had the Baroness who had put him

up in her country estate, but both were disappointed when, after the war,

hoping to renew their acquaintance with him, he failed to respond, a curious affirmation

of how much he had been wounded by his German experience, and was determined to

put it behind him.

Later he

was permitted to go to occupied Paris, where he was when the war ended. He then

turned himself in to the British authorities, who sent people to interrogate

him, as was done with other British subjects who had spent the war in Germany.

The first interrogator was Malcolm Muggeridge, who immediately fell under his

spell, and declared the fuss about the broadcasts was nonsense. Later came a

Major Cussen, who was persuaded of Wodehouse’s innocence, but who turned in a report

that, while exonerating him, was no whitewash, as McCrum writes. Cussen

concluded that “a jury would find difficulty in convicting him of an intention

to assist the enemy.” Finally, the French government cleared him, and he was

free to go. He decided to go to the United States, and never set foot in

Britain again.

It

summarizes Wodehouse’s attitude towards the world he found himself in that when

he was arrested by the Germans in 1940 he was within four chapters of finishing

Joy In the Morning which many aficionados of his work regard as

his greatest novel. And while Churchill was warning the British that he could

offer them nothing but blood, sweat and tears, and urging them to fight on the

beaches, landing fields and so on, this dedicated artist, for whom the work

always came first, was engaged in

finishing a narrative of, as he says on page one of the book, “the super-sticky

affair” of Nobby ‘Stilton’Cheesewright, Florence Craye, his Uncle Percy, J.

Chichester Clam, Edwin the Boy Scout and old Boko Fittleworth --- “or, as my

biographers will probably call it, the Steeple Bumpleigh affair.”

By 1942, in

the throes of the worst turmoil of his life, Wodehouse began thinking about the

plot of The Mating Season (my

favourite book), and its dramatis personae of “a surging sea of aunts,” who

occupied Deverill Hall, with Bertie undertaking a task imposed by his Aunt

Agatha (“who chews broken bottles and kills rats with her teeth,”), namely, to

ensure that Catsmeat’s fiancee Gertrude remain true to him, while promoting

among the aunts the idea that Gussie Fink-Nottle (“goofy to the gills, face

like a fish, horn-rimmed spectacles, drank orange juice, collected newts”) was a worthy catch for Madeleine Bassett

(“England’s premier pill.”). The motivating factor for Bertie, the narrator,

was, as usual, that he had previously been engaged to Miss Bassett, and could

consider himself safe only so long as she was affianced to someone else: because the moment she was free of such entanglements, she was poised to make herself available

to Bertie, a helpless victim who she mistakenly believed was pining away for

her.

These two

books are described by Mr. McCrum as the main wartime production of this remarkable writer who allowed nothing to get in the way of his work. Need anything more be

said? The man was a genius, a great writer, an innocent, and as sweet a guy as

ever trod the earth. He was awarded a knighthood at New Year's 1975, a symbol

that all was forgiven at last, and he died within six weeks at the age of 94.

He was found sitting in his armchair with a pipe and tobacco pouch in his

hands, the manuscript of yet another unfinished novel close at hand.

No comments:

Post a Comment