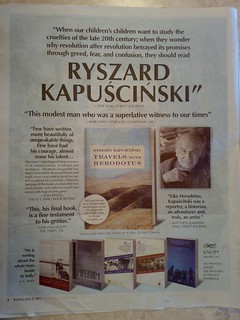

| Ryszard Kapuściński (1932-2007), Polish writer and journalist (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

| Ryszard Kapuscinski (Photo credit: teachandlearn) |

I have

just read a fascinating biography of the remarkable Polish journalist Ryszard

Kapuscinski, a book first published in Polish in 2010, three years after the

journalist’s death, and in English last year. The book by Artur Domoslawski,

received rapturous reviews in English, but was the subject of a law suit issued

by Kapuscinski’s widow, who claimed it defamed the writer and invaded his

privacy, and as a result of which the book was withdrawn from circulation by

its publisher Verso, a left-wing

publisher of New York and London.

This is a

shame because although the book does investigate, among other aspects of the journalist’s

character, certain aspects of his attitude to precise truth, it is written in

such a sympathetic way as to leave no doubt that the author Domoslawski was an

admirer --- one might say, a fervid admirer, like so many others who knew him

--- of the journalist and his works.

An

especially fascinating aspect of the book is the detailed description of the relationship

between the free-wheeling foreign reporter exercising his genius on the

problems of modern Africa, Asia and Latin America --- to the eventual admiration

of the entire world --- and the Communist party functionaries to whom every word

he wrote had to be acceptable..

Kapuscinski

was born in 1932 in a small town that is now part of Belarus, the son of

primary school teachers who, during the war, moved from place to place to avoid

the possibility that they might be deported to the East. The child had a

standard education, showed some talent at writing poetry at an early age, and

at the age of 16, before he had graduated from high school, joined the

recently-founded official Communist youth organization, the ZMP. Two years

later he began working for a Youth newspaper, a job he suspended for five years

while he studied at university. When he was 20 he married a girl who later

became a doctor and was his wife for the rest of his life, and who had to live

through his long absences from home as he toured the world.

He became

a member of the Polish United Workers’ Party, the governing Communist party,

and by this time was a firm believer in Communism as the hope for a better,

more equal Poland.

He was only

24 when he was sent on the first of many foreign assignments. At first he

worked for a succession of journals, or newspapers, and later for the Polish

News Agency. All of these fell under the control of the Central Committee (of

the Party) press office, whose official line fairly rigorously followed the

official line set in Moscow. Therefore every variation from the official line

had to be debated by the apparatchiks of head office, and from the first

Kapuscinski’s writings raised severe

questions for these bureaucrats.

From the

first, equally, he had been careful to make friendly contacts with well-placed

people in the party regime, and equally from the first he supplemented his emotionally accurate reportage with bulletins intended not for

publication but for the eyes only of

people who needed to know what was going on in the area he was covering.

In one of his earliest years, he wrote 15 of these bulletins, which were

apparently well received, and fended off the very lively possibility that his brilliant reportage might have

opened him to accusations of disloyalty to the ideals of Communism.

He never

had an easy time of it as a foreign correspondent, because two or three

publications for which he wrote and the news agency were always short of money,

and in any case paid extremely low wages. He was paid $300 a month, which was,

as the author says, “peanuts” for a roving reporter expected to cover the whole

continent. This was so more particularly because from the first Kapuscinski was

fascinated by the unique qualities of African life, appalled by the colonial

history Africans had had to suffer over many decades, and temperamentally sided

always with the underdog. So he fell in love, as the author describes it, with

the idea of revolution, and wrote in support even of revolutions --- Che

Guevara’s efforts in Bolivia were a prime example --- that were regarded as

almost anti-party foolishness by the big shots in Moscow, and even by his immediate

bosses in Warsaw.

He soon

became renowned in Poland for his unusual detailed reporting, which concentrated on the people at the grassroots level of anything he was describing, but his world

fame did not come until his remarkable book on Haile Selassie was published in

an edition of 5000 copies in New York. It was received with unanimous acclaim

by critics, but even that on such a remote subject of little intrinsic interest

to Americans did not guarantee sales of more than a few thousand of the second printing.

Nevertheless, this was the beginning of Kapuscinski’s global fame, which escalated

with the publication of each of his books. His basic subject was the ending of

colonialism in Africa Latin America, Central America, right up to the collapse

of the Soviet Union.

Domoslawski

goes into some detail about what critics have felt was Kapuscinski’s free and

easy way with basic facts. He argues, first, that he created himself as a principle

character, inventing a busy military career for his father for instance,

and later carefully creating an image of himself as a correspondent

who was present at some revolutions that he actually wrote about only after the event.

And also, he says, the journalist, an imaginative fellow, invented some of the

details that he reported; for example, he reported that a small dog owned by

the Ethiopian emperor was allowed to piss on people’s shoes, for which a

special courtier was retained to follow the great man everywhere and wipe clean

the misdemenors of this dog. That courtier apparently never existed.

This is

why Kapuscinski called his style of reporting “creative reportage”, a method of

recording what was happening before his eyes that placed him in a category something

like that of Hunter S. Thompson, who had a tendency to invent false information

about politicians he disapproved of.

I don’t

think Kapuscinsi did that quite so blatantly, but he was regarded as something

of a fantasist, and regarded people like Gabriel Garcia Marquez, inventor of

“magic realism” who became one of his most fervent admirers, as an important

influence.

After his

death, some diligent researchers in the period known as “lustration” --- that

is, revealing from the archives the crimes committed by prominent people during the years of authoritarian governments

--- accused Kapuscinski of having worked for the intelligence services.

Domoslawski deals with this accusation in detail: his examination of the

archives shows that, indeed, Kapuscinski was recorded as a willing informant

for the security services, but in fact he never reported anything to them that

was not already easily available to everybody. His position in this regard was

equivalent, as the author points out, to some 400 American reporters and their

governing agencies, who are known to have collaborated with the CIA. So, it is

safe to say that all efforts to besmirch the name of this exceptional reporter

and literary artist have failed miserably, and he continues to be viewed with

something approaching adoration around the world. In his lifetime --- he died in

2007, at the age of 74 --- his books were published in the languages of

countless countries, he was an invited

lecturer in at least 13 universities and received countless awards and was

spoken of as a likely future recipient of the Nobel Prize for literature,

something he never lived to see.

Another

interesting section of this biography is where the author attempts to isolate

from Kapuscnski’s voluminous writings exactly what were his attitudes towards the

modern world. This shows that his basic approach

was that 20 per cent of the world’s population are privileged, and 80 per cent

are not. Therefore it is evident that in the future these 80 per cent will be

demanding their share of the fruits of the earth. He was proud of having given

to these 80 per cent a voice that previously --- and indeed, in most places,

until this moment --- they have not had.

I want to

add a personal note to this. Without wanting to make any comparison between my

own lifetime in the media of the Western world and the dazzling career of this

great reporter, I was interested because I could identify with much that he

went through. I appreciated how he managed

to find a method of describing reality that would not offend his bureaucratic

bosses. That was a much tougher situation than anything I had to confront

during my own career: but the fact is, for anyone like me who did not agree

with the politics of the newspapers and agencies for which I worked, many

stratagems similar to those used by Kapuscinski were necessary. As I have

written elsewhere, I had to become skilful in suggesting things that I did not

have the freedom to write directly. My attitude to my colleagues and their

belief that they were exercising freedom of expression is that I felt they were

self-deluded. The most abject followers of the capitalist programme of their

newspapers or agencies would have been amazed if they had at any moment tried

to write something in favor of, for example, socialism, or the trade union

movement, as distinct from the party-line capitalism, whose parameters they

knew and observed meticulously.

I identified

with Kapuscinski’s attitudes when he arrived among the people of the colonial

regimes in Africa. At around the same time as he was discovering them, so was I

on various trips I made. And the description given of one of his friends arriving among the the white populations of Africa closely agree with my

own observations:

….the

whites they meet in Tanganyika are “ghastly, even in terms of facial

appearance,” whatever the nationality: Germans, Britons, Belgians, Poles…. Abominable

types, losers who flocked to Africa because things hadn’t worked out for them

anywhere else, upstarts, exploiters of the local population, and, without

exception, racists. They run bars and hotels --- they are ‘petty businessmen’.

One of the people they encounter goes about with a monkey, because ‘he’d rather

drink with a chimp than a black.’ These

are the typical remnants of the colonial class whom Kapuscinski encountered in

Africa: the face of Europe, which came to Africa to ‘spread civilization among

the savages.’

I had much the same feeling when I visited Southern Rhodesia in the 1960s. And in a

later book Kapuscinski writes:

The

philosophy that inspired the construction of Kolyma and Auschwitz, one of

obsessive contempt and hatred, vileness and brutality, was formulated and set

down centuries earlier by the captains of the Martha and the Progresso, and the

Mary Ann and the Rainbow, as they sat in their cabins glaring out the portholes

at groves of palm trees and sun-warmed beaches, waiting aboard their ships anchored

off the island of Zanzibar, for the next batch of black slaves to be loaded.

Overall, Domoslawski

gives full recognition to Kapuscinski’s charm, his gentle manners, the fact

that he was a magnet for tens of thousands of eager young people anxious to

learn more about the world, people not afraid to confront “the other” ---one of

Kapuscinski’s favorite subjects, learning to get along with everybody, which,

he said, lies at the basis of any possibility for a successful future.