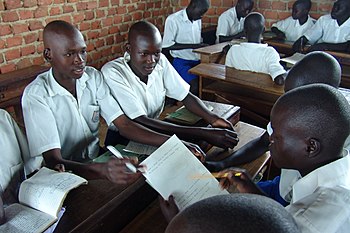

| Students in Uganda: the target of the evangelicals (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

| Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni, Entebbe, July 2003 (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

| English: Uganda (orthographic projection) |

If

I thought there was too much religion in the film about Haiti that I wrote

about yesterday, imagine how I feel about the film on Uganda that I saw last

night!

Cinema

Politica Concordia, that is living up to its reputation for producing timely

information on matters of importance, managed (by happenstance, I imagine) to

screen a film about the American-induced hatred of homosexuals imposed on and

in Uganda, just one day after the Parliament there passed a homophobic law that

would imprison homosexual practitioners for up to ten years.

The

film God Loves Uganda, was screened in the context of a

parallel festival of films of LGBT Afro-Caribbean interest by a

group called Massimadi. The reference to Love in the title of Roger Ross

Williams’ film is ironic, of course, since there is nothing about love either

in the film, nor in the attitude of the American evangelists towards their

fellow human beings.

In

fact, these people, who have all sorts of totally absurd beliefs, such as that

the Bible contains the literal truth, actually pour out hatred for anyone who

doesn’t believe them, and they call it Love. The film is ostensibly about the

homophobia that has seized Uganda, but the story is told by concentrating

attention on the Kansas-based International House of Prayer that has taken unto

itself the duty of imposing their ridiculous views on the rest of the world.

So, they train young people as missionaries and send them out to establish

beachheads from which to preach their disgusting beliefs. That they seem to

believe what they say doesn’t make their activity any more praiseworthy.

The

film used spokesmen from both sides of this war, and those on the side of

tolerance and decency expressed themselves as ineffably saddened by what they

have seen happening in their country, while on the homophobic side the

preachers, even the homegrown Ugandan preachers, have

grown prosperous and disgustingly wealthy, as they divide their time

between palatial homes they own in various American cities and Kampala, capital

of Uganda.

I

have always had an interest in the fate of Uganda, arising from a time I spent

in London unemployed during seven months in 1951. At the time, desperate for a

job, I wrote to places and people around Britain, and around the world. One of

the places I wrote to was Uganda. I had worked in Invercargill, New Zealand in

my first job as a journalist with a man whose brother had been one of many

Rhodes Scholars produced by the High School I went to. This man had come out of

his studies at Oxford with distinction, and subsequently joined the

British colonial service. He was getting close to retiring after a 20 year

career in Uganda, which at that time was believed in Britain to have a model

colonial administration, forward-looking and progressive (so long as one could

say that about any colonial administration), under the guidance of Sir Andrew

Cohen, the governor, who arrived in Uganda after a much-praised career in

several British colonies.

The

man to whom I wrote in search of a job did write me a friendly letter in

return: I remember he remarked on how they seemed to be progressing well under

a masterly leader who, it seems, had been mandated to prepare the colony for

self-government.

How

ironic that when the transition to independence did arrive in 1962,

Uganda should have almost immediately have become the poster-boy for failed

African self-governing administrations. Indeed they were not just failed

governments, these governments of the newly independent colony, they were

governments of almost indescribable horror, especially that of Idi Amin, the

semi-literate soldier who took over from the failing government headed by

Milton Obote. Amin was eventually removed from office by the army of

neighbouring Tanzania, who re-installed Obote, whose second administration

turned out to be almost as disastrous as that of his predecessor. Out of the

chaos of these changes, in which Obote was also removed by a coup,

after fighting a guerrilla uprising in which an estimated 800,000 people were

killed, the present president of Uganda Musaveni emerged from the bush to

establish order and set the country on a ore correct path. But, having been in

power since 1986 --- a mere 28 years --- this model reformer is now himself

hanging on to power like a limpet. And he is the president who signed the

anti-homosexual law this week. Thus he appears to have long outlived the hero

status he acquired from his success in rescuing Uganda from its decades of

lower-depths grovelling under a series of squalid dictators.

I

have one other personal anecdote that might add a little flavour to this

account: in the mid=fifties, when I was for a year a student at an adult

education school in Scotland, we received one day a visit from a distinguished

(and very impressive) African woman whose name somehow has stuck with me to

this day. Pumla Kisosonkole carried with her all the dignity one associates

with the leadership type of African women. I seem to recall she professed to be

a supporter of the Kabaka of the Buganda --- the King, as it were, of the

largest tribe in Uganda --- a man who not very long after her

visit declared his tribe independent of the colony and was exiled by

the governor for his pains. When Ugandan independence did arrive, he was the

first president of the nation for two and a half years until being replaced by

Milton Obote.

As

for Ms Kisosonkole, I learned only yesterday from the Internet that she was a

South African who had married in 1939 a Ugandan and had gone to live there. She

had not only become the first African woman to serve on the pre-independence

Legislative council, but had later become president of the International Council

of Women, Ugandan representative at the United Nations General Assembly for two

years, and later a literacy expert at UNESCO.

I

mention all this to indicate that Uganda was, indeed a promising place in its

pre-independence phase, and was not the sort of place that one would expect the

people could be so completely taken over by vulgar right-wing American

fundamentalist preachers, as seems to have happened in recent years.

The picture painted by

last night’s film was a rather desperate, depressing one: but two of the

pro-homosexual spokesmen did manage to shed a ray of light. One young Anglian

priest who spoke out against the evangelicals, Rev. Kapya Kaoma, spoke

throughout the film from his self-imposed exile that he undertook when it became

clear to him his life was in danger if he stayed in his home

country. Towards the end of the movie the funeral occurs of David

Kato, the first Ugandan to “come out” with an admission of his homosexuality

and was beaten to death. A former Anglican bishop Christopher Ssenyonjo who was

defrocked by the Anglicans for defending homosexuals, said that at the church

service over Kato’s corpse, he heard a member of his Church say

homosexuality was evil, so he determined to go to the graveside where

he made a short, dignified --- and I would think, extremely brave --- statement

in defence of the right of homosexuals to live their lives like other human

beings. Against all the evidence of the film, this man expressed mild hope for

the future, a hope that this madness will eventually pass.

Understandably

because of the crisis nature of events in Uganda, the film emphasized the

homosexual angle. I personally would have preferred if it had included the

danger to everyone, homosexual and straight alike, of these dire sects and

their fanatical behaviour. To realize the completely nonsensical stuff these

people are peddling, one has only to hear the ravings of Scott Lively,

the American missionary who, as Kato observed, in the U.S. would be a

bush-league wacko heading a small right-wing ministry, but in Uganda somehow

gets to address the national Parliament. Part of his schtick is that gays

caused the Holocaust, although the how of it is left as a yawning gap.

No comments:

Post a Comment