|

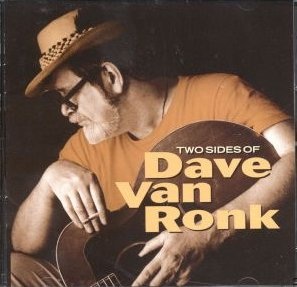

| Two Sides of Dave Van Ronk (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

| Ramblin' Jack Elliott in London (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

| English: Coen Brothers at Cannes in 2001. (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

I have always believed that film should be a weapon in the

class war, that thing that is so unfashionable in the Western industrialized

countries these days, because we have fallen so totally into the control of the

corporate state. Class war presupposes strong unions, militant protesters,

movements at every level of society to get back control of events into the hands

of the people.

Defined like that, of course most modern films, especially

feature films, fall short. The feature

film industry is dominated by the immense amounts of money required to even get

a feature film underway, and to be frank, one can count on the fingers of one

hand the number of feature films of the last ten years that could be viewed as

fulfilling my objective of being a weapon used for the education of their

audiences.

These reflections arise from my viewing yesterday of the

newest film from the Coen Brothers, who are masters of film-making, but have

always appeared to me to have no other agenda except just to get the films made,

regardless of their ultimate social meaning.

Though they deal with socially significant subjects, I

usually am left with a slightly empty feeling in that they seem to have no

attitude towards the subjects they spend so much money and so much attention,

in delineating.

Their newest offering is called Inside Llewyn Davis, a brilliantly made portrait of a folk-singer,

who, although talented, keeps fucking

up, if I may be permitted such a colloquial expression. The film is said to be

based on the real life of a folk-singer called Dave Van Ronk, with a nod to

other folk-singers of the early sixties, including one called Ramblin’ Jack

Elliott. I have never heard of Van Ronk (the film’s title seems to have been

borrowed from an album called Inside Dave Van Ronk) and the producer

brothers seem to have strained to capture the authentic sound of folksong, by

casting Oscar Isaac, a Guatemalan-Cuban-American actor with a folk-singing

background, who certainly does a great job.

Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, however, has swum into my ken

recently because in the early 1960s he turned up in London, and became a

regular performer at the Troubadour café, about whose early years I have

recenty written a small book. Elliott was an immediate success with his

easy-going, cowboy style. After spending some years in England he apparently

returned to the U.S. to find his reputation considerably enhanced by his

success in Britain.

The problem I have with this film is that the character

portrayed kept making mistakes, simple mistakes, such as locking himself out of

his apartment, finding himself lumbered with the cat of friends which he was

supposed to be looking after but that he foolishly allowed to run free, constantly

trying to borrow money to deal with the pregnancy of the wife of one of his

best friends whom he himself appears to have possibly had some influence in

making pregnant, and going off without money enough to support himself on a

trip to Chicago to consult with a producer whom he fruitlessly hoped might have

liked his last album. Just errors of

judgment at every turn. All of this could have been avoided with the exercise

of a modicum of common sense which one would have supposed the character to

have, in normal circumstances.

But leaving that aside, the film coud be said to be an

accurate representation of the problems of a talented but undisciplined artist

caught in a money-obsessed society to whose obsession he felt inimical. Even

so, the film-makers’ distance from their character and his peripatetic life

seemed to weaken the impact that the film might have had, given a warmer

approach.

This reminded me of one other Coen brothers film that I

really heartily disliked, the Academy Award-winning No Country for Old Men. This was a portrait of a psychopathic killer

who went through life casually killing people, without a single modicum of

explanation offered the audience as to what he thought he was doing, why he was

like that or any coherent explanation for his unacceptable behaviour. What

offended me more than the shortcomings of this film, hOwever, was that Hollywood

saw fit to award its highest honour to the film, although it had available the

masterpiece There Shall Be Blood, the

superb film based on the early chapters of an Upton Sinclair novel about the

oil industry. The film was literally a history of early predatory capitalism,

and the sort of psychopathic behaviour that went into creating that heartless,

killing industry. Graced as it was by yet another marvellous performance by

actor Daniel Day-Lewis, this was so obviously a superior product as to make my

argument outlined in the first paragraph of this piece. This was a film designed

to educate, as well as move and entertain, an audience, and it could not have

stood in harsher contrast to the modus

operandi of the Coen brothers. That it was the brothers’ offering that was

given the accolades was as clear a statement as we will ever have of the

underlying social assumptions of the Hollywood industry, even in these

relatively enlightened days.

And that is my same reservation about this film. I am

maybe hoping for too much, looking for a revolutionary in every director.

No comments:

Post a Comment