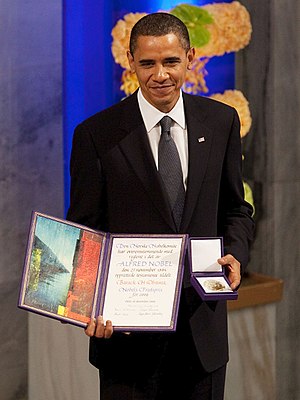

| English: President Barack Obama with the Nobel Prize medal and diploma during the Nobel Peace Prize ceremony in Raadhuset Main Hall at Oslo City Hall in Oslo, Norway, Dec. 10, 2009. (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

There may be something wrong with me, but whenever I hear

--- as one does nowadays almost every day --- the political leaders of the

United States waxing indignant at the use of chemical weapons, one question

keeps popping into my mind: “Would you have so enthusiastically recommended

international action to stop the United States from poisoning Vietnam with

Agent Orange?”

After all, in the use of chemicals as a weapon of warfare,

the U.S. must take the cake. Not only did they set out to destroy the very land

on which the Vietnamese people lived, but they sewed chemicals and their deadly

effects so successfully in that soil that children born years after the war had

ended are still ending up with horrible physical and mental deformities.

Of course, this is just one aspect of the hypocrisy that

seems uppermost in almost every decision taken by the powerful “in these

days,” if I may quote Dorothy Parker,

“of horror, despair and world change.”

It is no news, of course, that the rules of justice are

dictated by those who win the wars, or, if they don’t win them, nevertheless

retain the preponderance of power. But the behaviour of Barack Obama, a

well-known student of constitutional law, in suddenly, on his elevation to the

presidency, turning into a hawk for war, was not only unexpected, but seems

completely hypocritical. Rebuffed recently

in his effort to drum up support for armed intervention in the Syrian civil

war, he and his mate John Kerry --- a veteran of the Vietnam war himself ---

have not shrunk back even a step, but are continuing to travel the world,

pressing other nations to support their decision to extend the war, even though

they must be aware of the fraught possibilities that could arise from such a

decision. It’s as if the Americans, having absorbed from the movies they saw as

children that the only answer to any problem is a good sock on the jaw, are now

expecting the rest of the world to have absorbed that message.

This guy got the Nobel Peace Prize?

This weekend the BBC screened a debate held in Australia

around the topic that “the United States is our (that is, Australia’s) best

line of defence.” Before the debate,

which featured the American ambassador in that country on the one side, and a

professor from the Beijing university, allied with a retired Australian

general, on the other, the audience was about a third for the motion, a third

against, and a third that had not made up its mind. After the debate, the

undecided had fallen to 10 per cent, the people against the motion has swollen

to an overwhelming 56 per cent. In other words, the arguments put forward in

such honeyed tones by the U.S. abmbassador did not go down well with that

Australian audience.

One thing that struck me was that when speakers, both from

the platform and the audience, spoke of “this region”, they were talking about

a part of the world that is almost as far from the United States as it is

possible to get, and yet there was the United States parading its belief that

it is part of their essential interests to set up a military establishment in

Australia. Australian governments, of course, have acquiesced, as they had

always done, largely, one would have thought, because of a continuing strain of

inferiority complex by the people Down Under (as we used to call ourselves in

that part of the world.)

The very reasonable-sounding professor from Beijing seemed

to have won over many in the audience when he said that the U.S. has surrounded

his country with nine military bases which made Chinese people nervous. The

ambassador coolly denied that these bases were in any way directed against

China, and said they had nothing but peaceful purposes. If that is how the

Americans customarily think of their global network of 840 military

establishments in every part of the world, it is no wonder that the ambassador’s

argument fell on deaf ears.

At one point the moderator had to remind the audience that

they were not gathered to collect grievances against the United States, since

so many complaints about U.S. presence were being expressed, but to consider the motion.

The debate illustrated one other thing, to my mind, which

was the efficacy of humour in argument, for the Austraian general, who had

served in the forces in Iraq, had the audience laughing quite often with his

good-humoured quips, all of which seemed to have gathered support for his

argument, as against the deadly serious argumentation offered by the other

speakers.

Of course, it is terrible that chemical weapons have been

used. I wrote my first article against chemical weapons in the late fifties,

when details of Canada’s own chemical weapons centre in Alberta at the Suffield

base, were just being revealed for the

first time. I remember commenting with some acerbity on the fact that a woman---

whose name I reemember after all these years, Dr. Dorothy Latimer --- had been

granted a medal by the United States government for her sterling work in

inventing some new chemical weapon designed to kill people.

But if the United States wants to demonstrate how thoroughly it opposes the use

of chemical weapons, perhaps they could put more resources into helping Vietnam

overcome the effects of the chemicals they dropped on the people, and the

plants, of their country, years before anyone in the Middle East had decided to

follow their example.

No comments:

Post a Comment