| African National Congress (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

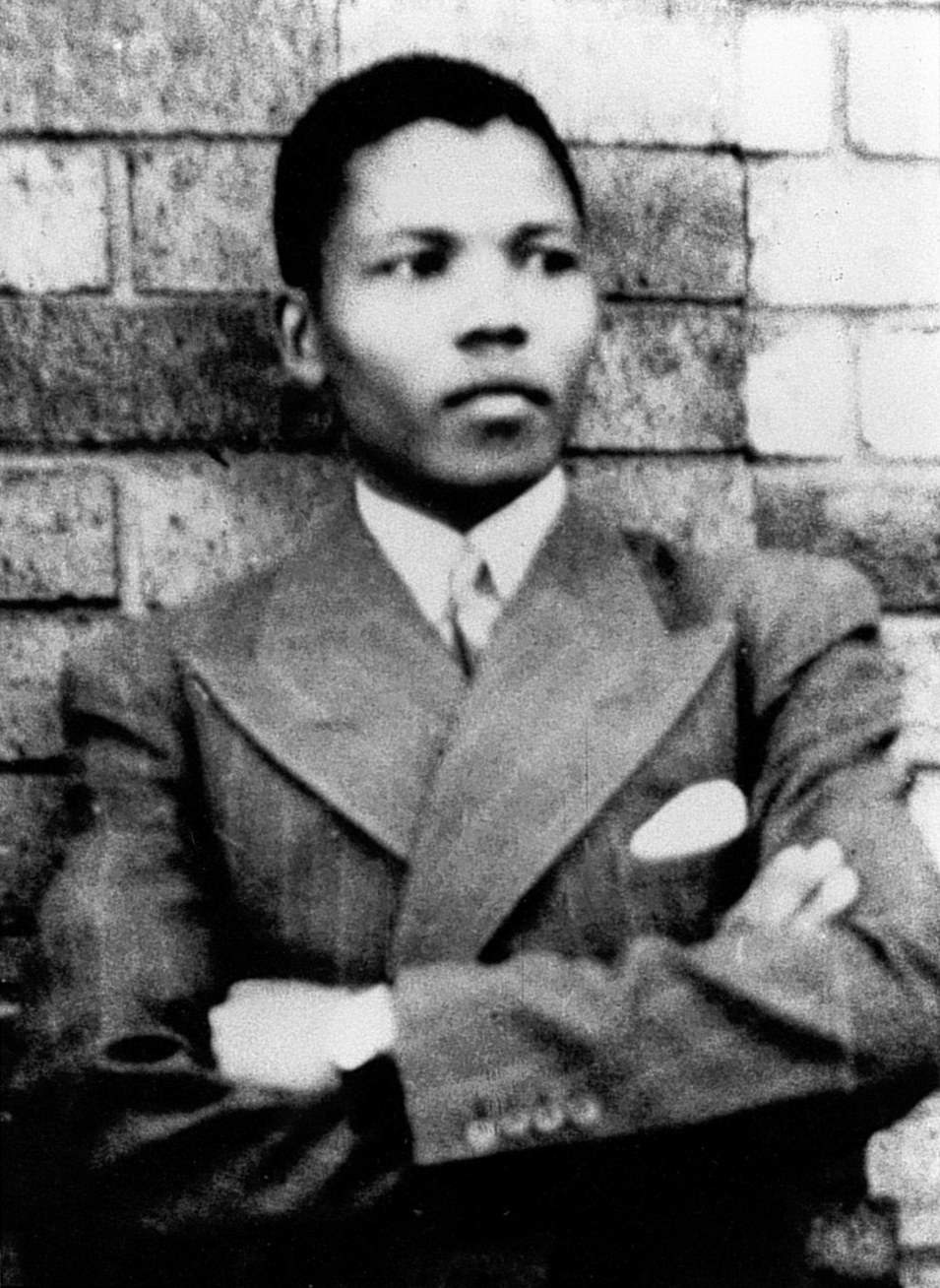

| English: Young Nelson Mandela. This photo dates from 1937. SImage source: http://www.anc.org.za/people/mandela/index.html (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

I notice today the BBC is celebrating the 50th

anniversary of the Rivonia arrests in South Africa, which has made me think of

my friendship with one of the arrestees, Harold Wolpe and his wife Anne-Marie.

The arrests were made in July, 1963, but Harold and his friend Arthur Goldreich

bribed their way out of jail, escaped South Africa, in spite of a frantic

search for them by the police, and on arrival in England at the beginning of

October headed for Blackpool (I think it was Blackpool) where the Labour Party

was in the middle of its annual conference.

There they appeared at a small meeting of leftist Labour

supporters. Goldreich was a spell-binding speaker who did not stay in England

for many months, but headed for Israel, where he died a couple of years ago at

the age of 82. I was so impressed by his presentation about the political

tyranny operating in South Africa that I arranged to interview Harold Wolpe

when I returned to London.

Harold’s account of his life during the previous 10 years

or so, when he had been the solicitor for

the leading activists of the African National Congress, was enough to

convince me that the route of armed struggle was all that had been left to

them.

Harold had won many cases for his clients in the South African

courts, but every time they won a case the government immediately changed the law

in such a way as to make it impossible for any more cases to be won. In this

way, the legal freedoms of assembly, protest and dissent were closed off one by

one, inexorably, over the years, until

Mandela and the other leaders decided to launch an armed wing of their by now

banned political party, all other avenues for protest having been closed to

them.

Arthur Goldreich was an artist working for a Johannesburg

firm, and the tenant of a farm, Liliesleaf, which he made available to Umkonta

We Sizwe, the armed branch that the African National Congress was in the process

of organizing and developing. Goldreich had been an activist even as a Jewish

kid of 11, when at his school the Afrikaans government began to teach them

German in the belief that the Nazis had already won the war. He protested,

successfully to the Prime Minister, Jan Smuts, and in 1948 he went to Israel to

take part in the Jewish armed struggle to establish that country. Because of

this experience, Mandela found him useful, for he himself had no knowledge of

warfare of any kind and needed advice in how to set up an armed resistance

movement. It was Goldreich who had drawn

up the programme for the armed group that was discovered when the security

police raided the farm, the rent of which was being paid by the underground

South African Communist party, of which Goldreich and Wolpe were both members. Most of

the leaders were arrested, including

such as Denis Goldberg, Walter Sisulu, although Mandela himself was already

imprisoned by this time.

Nevertheless Mandela was included in the people charged at

what came to be known as the Rivonia trial, from the consequences of which

Wolpe and Goldreich managed to escape, but which culminated in Mandela’s life

imprisonment.

At the time I interviewed Wolpe I was London correspondent

of The Montreal Star. According to

the myths of Western journalism, I should have been neutral as between the

oppressive apartheid regime and its victims, but henceforth I had no doubt

where my loyalties lay, and I became a close friend of some of the activists

representing the ANC in London during those years. Particularly I admired their second most senior representative

abroad, after Oliver Tambo, whose name was Robert Resha. He had wanted nothing more than to be a sports

reporter, but had been made into an activist by being arrested some 28 times for

pass-offences --- that is to say, for not carrying at all times the passes

identifying every non-white person in South Africa. He had been a leading

volunteer in actions taken over the years by the ANC, and he was, as the sports

writers often say, the sort of guy you would want to have on your team in any

fight.

Through my friendship with Robert I learned what a terrible job it was to

represent a black protest movement, no matter how admirable, how democratic its

structures, or how incontrovertible its case for freedom. They had virtually no

money, and Robert’s job was to go around the world persuading people and

organizations with money to make a little of it available, and working to get

sympathetic resolutions passed through United Nations bodies. Even when this

succeeded, it seemed like a kind of pointless success, for these resolutions

had absolutely no effect on anything, except, probably, to begin the snail-like

process by which the apartheid regime finally began to feel its isolation in

the world. This was a tough slog: Scandinavia was the only corner of the world

responsive in any way to his appeals. Africans may have been sympathetic, but

they had no money. He told me often how he would approach Haile Selassie in

Ethiopia who would express maximum solidarity and support, but when the time

came offer maybe $5,000.

Robert sent his wife and their daughter to Moscow for

education, which meant that the cause broke up and took over his family life.

This process of a family neglected in favour of a cause apparently was

described in somewhat embittered detail by Anne-Marie Wolpe in a book she wrote

about her experience as a political wife, The

Long Way Home, which she published in 1994, after her return to South

Africa.

I returned to Canada in 1968, and when I passed through London briefly early in 1974 I arrived just as

Robert’s friend and sidekick Raymond Mazizwe Kunene, a noted Zulu poet and

political activist (who was another

close friend of mine during my London days), was working with Canon John

Collins at setting up a memorial service for the recently deceased Robert in

St.Paul’s Cathedral. It seemed a curiously bitter note, to me, that Robert in

the end had had a falling out of some kind with ANC policy, and his death and

lifetime of work for the cause was noted in only two lines in an ANC

publication.

Harold and his wife spent 30 years in exile in Britain

before returning to take up academic appointments in their homeland in the 1990s. There, they both became

renowned as original Marxist, (Harold) and feminist (Anne-Marie) thinkers whose

work has helped chart the way forward for their country. Harold died in 1996, and is still remembered

for the foundation established in his memory, the Harold Wolpe Memorial Trust,

and the annual Harold Wolpe Lecture sponsored and staged by the Trust.

As a BBC reporter noted this morning, the anniversary of

the Rivonia arrests seems all the more poignant for being celebrated as Nelson

Mandela is hanging on to the last days of his life in his mid-90s, his stature

among global politicians indicated by the world-wide anxiety that we are all about

to lose a man of uniquely inspirational moral quality such as our world has

seldom seen.

No comments:

Post a Comment