|

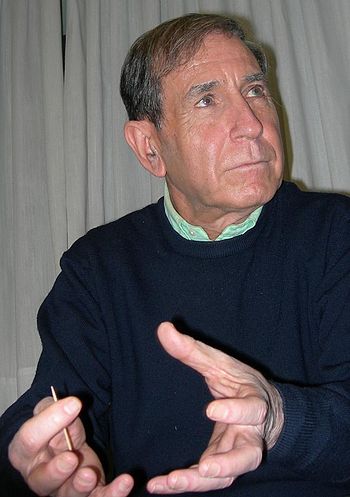

| English: Meeting in London against identification cards in the UK, on 2 July 2005. From left to right Tony Benn, Shami Chakrabarti, ?, George Galloway (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

| James Keir Hardie was an early democratic socialist, who founded the Independent Labour Party in Great Britain (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

| Plaque recording the location of the formation of the British Labour Party in 1900. (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

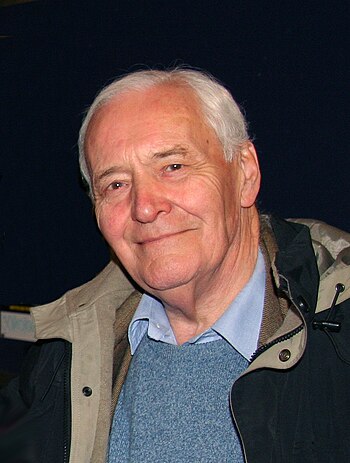

| Portrait Picture of Tony Benn (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

The British left-wing

leader Tony Benn who began life as Anthony Wedgwood Benn, then was elevated to

become Viscount Wedgwood when he inherited a peerage granted to his father, and

who renounced the peerage and actually changed these matters for ever in

Britain by successfully arguing his right to renounce his peerage through a

complex and somewhat antiquated legal system, has died at the age of 88.

His death has evoked

an outpouring of tributes to a man whom many regarded as the last of a dying

breed, a man who knew what he stood for, and who had mastered brilliantly the

art of telling people exactly what it was.

I spent eight years

of my life writing about politics in Britain, and at one point in the 1960s I

was commissioned by The Sunday Times ---

at that time one of the best newspapers in the English-speaking world --- to

write a profile of this controversial politician.

So I met him several

times, interviewed him at some length, and talked to others who were friends

and political enemies, and from it all I developed an intense admiration for a man

who always stood on the side of the poor and disadvantaged and who was so

positive in nature that he instilled hope in hundreds of thousands of people

--- as is evident from the many ordinary people who have written to newspapers

expressing their admiration for him over this weekend.

When I wrote my

profile he was already being treated by the right-wing as a leader of what they

called “the loony left” --- a habit that grew in succeeding generations, as he

watched his beloved Labour Party basically turned into something else, a

different party espousing different, more right-wing ideas, when it was taken

over by Tony Blair, a man whom he along with many others never considered to be

a left-wing leader.

At the time he was

just approaching a peak in the role

consigned to him by the establishment, that of a half crazy believer in the

outmoded --- as they saw it --- doctrine of socialism, the very doctrines that

had stimulated the formation of the Labour Party by the British trades union

movement at the beginning of the last century.

On the right there

was a similar bogeyman, Enoch Powell, whose warnings against the impact of

colored immigration into Britain were already resounding among people of that ilk.

But Powell was a considerable man, an intellectual not to be brushed aside lightly,

and he had been a friend of Benn when they were both members of the House of Commons.

Enoch Powell told me:

“He is the greatest master in Britain of the ethical sermon” --- a verdict so

demonstrably right on the mark as to be almost astonishing.

Benn told me: “I have

always thought that the accession to power of a Labour government in Britain

should be as much as possible like Castro marching into Havana”. A quote that

encapsulates his enthusiastic radicalism, his slightly naïve optimism, and his

determination to be to the left of everyone else.

As part of my

research for the piece I read most of the transcripts of he case he argued in

court for the renunciation of his peerage

He and others told me he had an unusual method: he seldom read books,

and depended on people in his support team to read them and tell him the

salient points. Thus, he had not read the actual ancient legal rulings relevant

to the cause he was defending; but his supporters in a neighbouring room were

keeping up with the argument, and were feeding him information that was likely

to be of use to him as the argument unfolded. So, when one of the ancient

judges would interrupt him, as they did on an average every ten minutes or so

over several days asking him about all sorts of abstruse legal points --- for

example, if the point he was making was not superceded by some ruling from,

say, 1642, Benn would be able to come back by saying, “That may be very true My

Lord, but was not that judgment itself modified by a later ruling delivered in

1723 (or thereabouts.)” This

extraordinary mental agility was at once his greatest strength, and possibly

one of his major weaknesses, My theory was that it meant for example, that

newspapermen of Fleet Street as it was then, found Benn hard to warm to simply

because he was demonstrably cleverer than they were, quicker on his feet as it

were, and ready always with a devastating rebuttal to any of their criticisms. One thing I learned about journalists during

my life among them was that they can be quite resentful of people who are

cleverer than they are, and I believed that explained a good deal of the bad

press that Benn normally attracted

He really believed,

when he was elevated to a minor position in the first Wilson government --- it

was Postmaster general --- that Labour should be carrying through a veritable

revolution in thinking about government and how it related to the people of

Britain. He told me, for example, that when the government declared a boycott

of the white-supremacist, illegal government of Southern Rhodesia headed by Ian

Smith, that really meant they should have no official dealings with that

government, Yet one day, across his desk came some document proposing

business-as-usual between the two governments. He stopped it right there. He

could not approve it because it violated the declared objective of the

government of which he was a member.

It was this aspect of

the man, that he meant what he said,

that is the characteristic most commented upon by people who have written to

the newspapers since his death.

The other admirable

thing about him was the clarity and forcefulness with which he expressed himself:

as one might gather from Enoch Powell’s description, he was a wonderful

speaker, and it is this, again, that hundreds of people have paid tribute to

this weekend: he could express himself with such clarity, his oratory was so persuasive

that it is clear from the hundreds of letters I have read that ordinary people

felt inspired by him, by the strength of his convictions, and the hopefulness

with which he always left his audiences.

Although when his political

career began 60 years ago he was an ordinary, moderate MP, as he developed his

oratorical skills and began to understand his place in British politics, he

became more and more radical.

Several people have

recalled that he had offered five questions he said should be asked of any

person of great power, whether /\Stalin,

Rupert Murdoch, Margaret Thatcher or anyone else.

1. What power have you got?

2. Where did you get it from?

3. In whose interest do you exercise it?

4. To whom are you accountable?

5. How can we get

rid of you?

Anyone who could not answer the last of these questions,

he said, could lay no claim to being a democrat.